By now, there is a fairly good amount of published books about the most famous professionals who started to ply their oars and sculls on the Tyne before they travelled the world for world titles and high wages, especially the latter. Of course, Harry Clasper and James Renforth are mentioned in the book, but in the first chapter Dodd writes about Jack Hopper of Hexham, a nowadays forgotten professional sculler (unless you remember Dodd’s article about him in the Regatta magazine of December 1987; which, as a matter of fact, I do).

Hopper, alias Smith of Scotswood, entered as a 20-year-old in the 1922 Newcastle Christmas Handicap with his eyes on the £100 prize money, quite a nice sum for a working lad at this time. He entered under both his real and false names to confuse the organisers and the other contenders. Though, this would be his first Christmas Handicap, Hopper was the fastest mover in any of the bookmakers’ books. He reached the semi-final, but there he was found guilty of a foul. He was also unlucky in the other Christmas Handicap races he entered, in 1923, 1924, 1927 and 1933. He never won any of these races, though he did reach the final in 1933 when he raced against Bert Barry of Putney, who, earlier in December that year, had beaten the Australian Major Goodsell for the world title. Hopper got a 15 second handicap, which would be impossible even for Barry to catch up. However, Hopper ran into the Redheugh Bridge – it seems his ‘flagger’ had lost him in the fog – so the world champion finished the race alone and claimed the prize money. Soon thereafter the handicap ‘fizzled out’.

Jack Hopper left an epitaph in 1983, Dodd writes. Hopper said: ‘As regards professional racing, there’s nothing honest about it, nothing at all.’

In the second chapter, before Christopher Dodd (on the right) embarks on telling the story of the famous boat builders on the Tyne, most of whom had been, or still were, professional rowers when they were crafting their boats and shells, he beautifully writes about the Tyne, Newcastle, its industries and the bridges in the city in a short account. When he gets to the boat builders, it is Matthew Taylor who starts the list. Taylor, a ship carpenter, who was hired by Royal Chester Rowing Club for £2:5s a week as a trainer in 1854, built an outrigger fixed-seat four, the Victoria, which had a smooth bottom, a boat with which the club took Stewards’ Challenge Cup at Henley in 1855. Taylor is credited for introducing the keel-less boat (that is with the keel inboard).

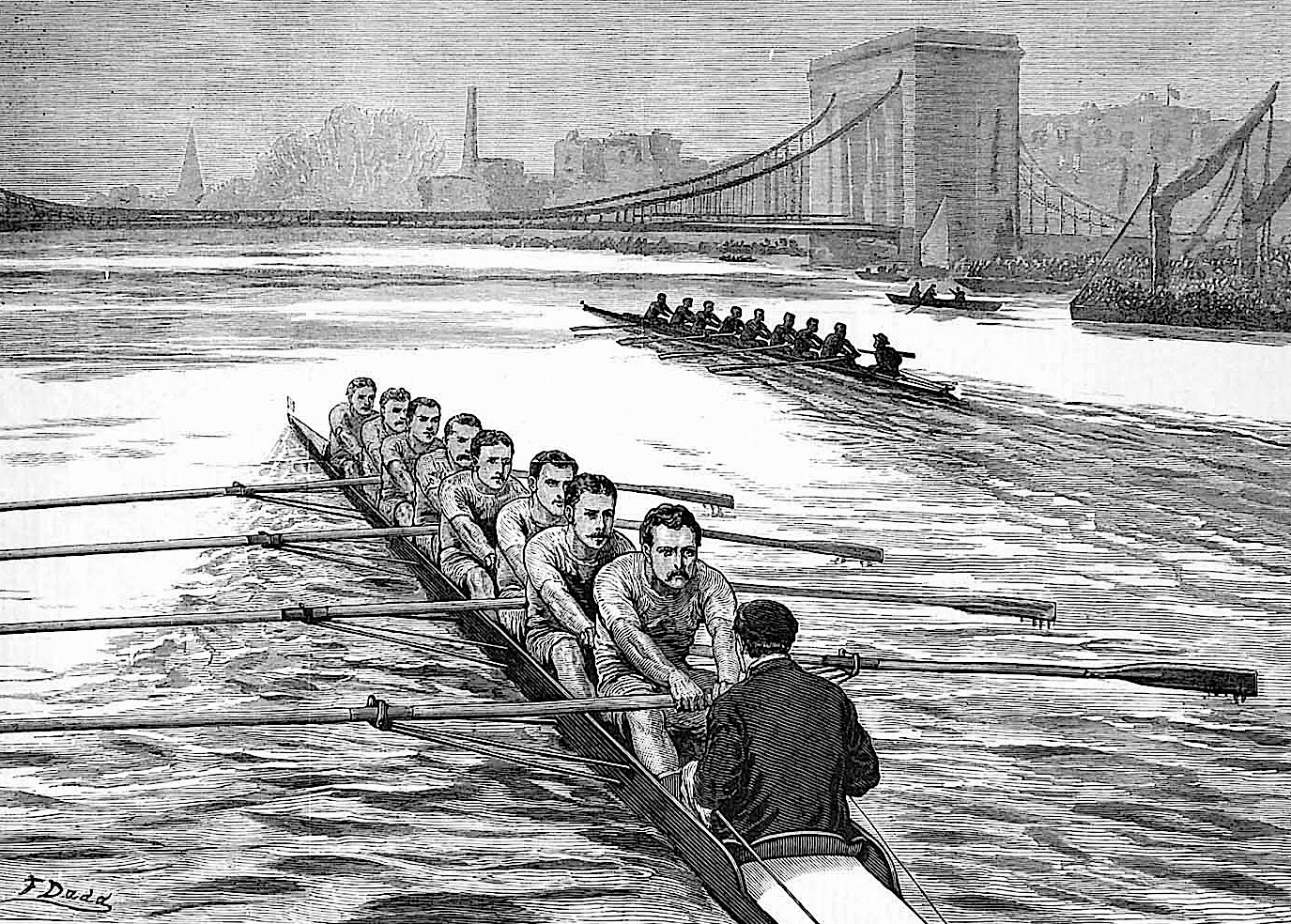

However, it is not certain that Taylor was the first one to build a keel-less boat, Dodd writes. J. B. Littledale, Royal Chester’s captain, stroke and benefactor, has also been claimed for the design, and so has Harry Clasper, whose son, Jake Clasper (a boat builder in his on right), once wrote that he coxed his father and his crew in a smooth-bottom boat at the Thames Regatta in 1849. Boat builder Robert Jewitt had a dispute with Clasper in a newspaper saying that he was the one, who in 1843, built a boat with the keel inboard. It is clear that we will never know who the first keel-less boat builder was. The Victoria – now at the River & Rowing Museum – is not the only boat mentioned in this chapter. Other famous ones, St Agne’s, The Five Brothers and Lord Ravensworth, to mention a few, are also to be found in this chapter. Another boat building company that is brought up is Swaddle and Winship, which built some famous eights for Oxford and Cambridge in the 1870s.

In “Pulling clivor on the coaly river”, the third and last chapter in Bonnie Brave Boat Rowers, we meet songwriters and singers whose songs were sung in pubs and music halls to celebrate the local professional sports heroes who by the 1860s were almost all oarsmen. As much as the writers praised the Tynesiders, they ridiculed the oarsmen from the Thames. Dodd writes: ‘They sold their latest works as pamphlets, and they did for Tynesiders what newspaper columnists, bloggers and chat shows do today.’

As the songwriters rejoiced in the local oarsmen’s victories, they dismayed in their defeat. When James Renforth, a former iron worker, who became world champion in the single sculler by beating the ‘southerner’ Harry Kelley on the Thames in November 1868, died at the oar during a world championship race in the four in Canada in 1871, the cable that reached the people by the Tyne was first not understood. The songwriter Joe Wilson, a friend of Renforth’s, wrote:

Ye cruel Atlantic cable,

Whay’s myed ye bring such fearful news?

When Tynesdie’s hardly yeble

Such sudden grief to bide.

Hoo me heart it beats iv’rybody greets,

As the whisper run throo dowley streets

We’ve lost poor Jimmy Renforth,

The Champein O’Tyneside!

It is always such a delight to pick up a book by Christopher Dodd, who is a master of telling stories. No one can spin a yarn of a rowing tale as well as he can. Not only is this little book incredibly well-written, some passages are even beautifully written. Congratulations and well done, Chris!

Do yourself a favour now, drop what you have in your hands, and order a copy of this book immediately – unless, you can wait till you are in Henley-on-Thames next time, which better be soon.

Bonnie Brave Boat Rowers is published by AuthorHouse: eBook: ISBN 9781491895535. Softback: ISBN 9781491895528.

eBook or Softback available from www.bonnierowers.com ; www.bookstore-authorhouse.com and all good book stores on the web.

Softback copies are also available from these shops in Henley: River & Rowing Museum, Richard Way Book Shop, Bell Bookshop, Leander Club, and Henley Royal Regatta, and all other good book shops.

Signed copies can be ordered direct from the author – send mail address and cheque for £9.95 plus postage (UK £1.17; EUR £3.70; Rest of World £4.75) to:

Christopher Dodd, River & Rowing Museum, Mill Meadows, Henley-on-Thames, RG9 1BF, UK

For more about Dodd’s books please visit www.doddsworld.org

This review was updated on 21 May, at 4:30 p.m., as I, in the first version, wrongly made Major Goodsell an American. He was an Australian, of course, which was kindly pointed out by Tom Weil ~ thanks.