Showing posts with label John Hawks Clasper. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Hawks Clasper. Show all posts

Monday, February 24, 2014

The Bonny* Boats of Newcastle

The Tyne God, the symbol of the River Tyne. A carving of such appears on a wall of Tyne Rowing Club in Newburn, near Newcastle.

Tim Koch writes:

A recent HTBS posting asked about Swaddle and Winship boat builders, a Newcastle-on-Tyne firm which built much admired racing boats in the 1870s and 1880s. I cannot produce anything like the full story of the firm, but I can provide some background to their work plus some (fairly random) aspects of their history.

Newcastle’s High Level Bridge on the River Tyne, the starting point for many famous professional sculling races.

To the casual observer of British rowing history, it would be easy to get the idea that very little has happened beyond Putney and Henley or Oxford and Cambridge and I am probably one of those who are guilty of promulgating this idea. I cannot correct this is in one posting but it is true that Newcastle-on-Tyne, an industrial city in the North East of England born of mining and ship building, has made a very large contribution to the sport of rowing and to the art (or science) of boat building. By the mid-nineteenth century, rowing on the River Tyne was a massive spectator sport among ordinary working people and a lot of money was changing hands through betting. Many improvements in boat design and in rowing technique came out of Newcastle, most famously from its three favourite sons, Robert Chambers, James Renforth and, in particular, Harry Clasper.

An early painting of Harry Clasper. Rather like the painting of another Newcastle sculler, Edward Hawkes, this picture appears to have had Clasper’s head added at a later date. The depiction of the boat cannot be taken as entirely accurate either.

Professional scullers were the first sporting heroes of the industrial working class (long before soccer players took this role). These oarsmen were not the ‘gentlemen amateurs’ of London and the south, they were tough working men who needed their boats to go fast so they could make the big money that gambling brings. Then as now, for many people with a less than privileged start in life, success in sport or show business was the only conceivable way to improve their lot. For this reason (and unlike many of the conservative amateur oarsmen) professionals produced or readily adopted new innovations such as outriggers, carvel hulls, sliding seats, swivel rowlocks, overlapping handles and keel fins and adapted their rowing styles to fit the new equipment. Further, it is mostly forgotten that for a long time England had two famous ‘Championship Courses’ for boat racing. One was the 4-mile, 374-yard Putney to Mortlake course on the Thames and the other was the 3-mile, 570-yard High Level Bridge to the Scotswood Suspension Bridge course on the Tyne.

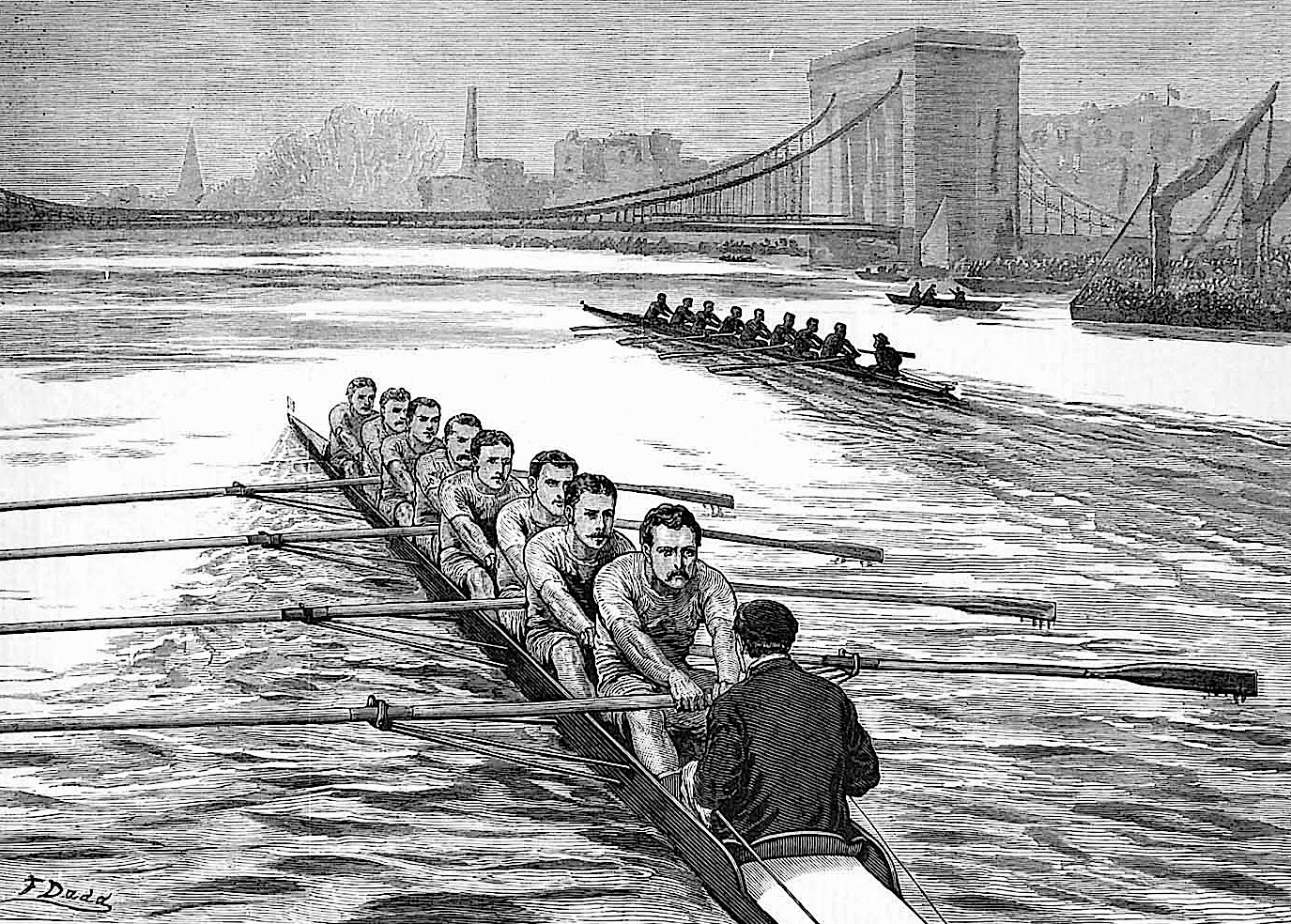

This illustration records a race typical of the calibre of those that took place on the Tyne Championship Course. After one of the greatest and most innovative of all scullers, Ned Hanlan, had become champion of Canada in 1877 and of the United States in 1878, he travelled to Britain in 1879 to take on the best the country could offer. The venue for his race against the English champion, William Elliott, was not on the Thames but was on the Tyne, before a crowd of 10,000. The Englishman used a Swaddle and Winship and Hanlan took two of the company’s boats back to the United States. The top picture shows the start at the High Level Bridge and the lower picture shows the finish at the Scotswood Suspension Bridge.

It should be of no surprise therefore that Newcastle should produce a highly respected firm of boat builders such as Swaddle and Winship. Rowing historian Eric Halladay held that by 1880 the three most important boat builders were John Hawks Clasper (a Newcastle man based in Putney), Sims of Putney and Swaddle and Winship of Scotswood, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

From references in The Times it seems that the Cambridge Boat Race crew used Swaddle’s boats from 1876 to 1883 and Oxford from 1878 to 1882. The firm’s ‘big break’ came in the 1876 University Boat Race when they built the winning craft. The quote below is from The Australian Town and Country Journal of 27 May 1876 (they may have taken it verbatim from a British publication such as Bell’s Life):

Cambridge (use) the new boat built for them by Swaddle and Winship, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, it having developed better qualities than their Searle boat... she is considerably lighter than their Searle... A novelty about the new ship is a somewhat peculiar arrangement of the ‘riggers,’ which dispenses with a consolable amount of the supporting woodwork and, as far as it can go, diminishes her weight... This is the first eight oar ever built in the north – at any rate in modern times – for either University, and should Cambridge win in her this year the firm of Swaddle and Winship is certain to become in great request, just as Clasper made his reputation as a builder by the boat in which Goldie first showed Cambridge the way to victory after a decade of defeat.

At least two of the eights Swaddle and Winship produced for the Boat Race became particularly well known, the Cambridge boat of 1877 and the Oxford boat of 1879.

Rowing historian Chris Dodd says this about the start of the 1877 ‘Dead Heat’ race it in his 1983 book, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race:

...the race started at 8.27am.... There was brilliant sun and a chilling wind, and Oxford had won the toss and chosen Middlesex, and were on the water first. Cambridge had a last minute panic about their Swaddle and Winship (boat). It was a short heavily cambered craft, and..... was very fast in calm water but stuck her nose into the wind if there was one, needing a great deal of rudder. The wind was from the west-northwest, the worst possible for Cambridge, and so they fixed a false keel to the boat at the last moment...

I am currently making a video for HTBS about the 1877 race and recently went to the River and Rowing Museum at Henley to interview Chris. To my delight, he produced what is alleged to be the bows of the boat made by Swaddle and Winship for CUBC in 1877. Unfortunately, it has no provenance beyond what is painted on it. It is illuminated with the names of the Oxford crew on one side and the Cambridge crew on the other. Both sides say ‘Portion of Boat used by Cambridge Crew. Dead heat.’

Allegedly the bow of the Swaddle and Winship boat used by Cambridge in the 1877 Boat Race. The Light Blue crew is recorded on the stroke (port) side....

... and the Dark Blues are on the bow (starboard) side.

As to the Oxford boat of 1879, The Times of 12 March 1884 had a report on a ‘sportsman’s exhibition’ held in London which included a display of racing boats.

The Oxford boat shown has been used in the (Boat Race) since 1879 [actually 1879 to 1882, TK], and is considered to be the best boat the Oxford crew has ever used. This was built by Swaddle and Winship of Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the same firm lent other specimens of boat building which have been used successfully in great races.

The 1879 Boat Race at Hammersmith. Between 1878 and 1882 both crews used Swaddle and Winship boats.

Of course, by implying that approval by the gentlemen amateurs of Oxford and Cambridge was the ultimate accolade, I continue to marginalise rowing outside of the south of England. My only (rather inadequate) defence is that the history of professional and north of England rowing has been sparsely recorded compared to amateur rowing in southern England.** Even successful amateurs from places like Tyneside are little remembered, men like William Fawcus of Tynemouth Rowing Club who won amateur sculling’s ‘Triple Crown’ in 1871 with victories in the Diamonds, Wingfields and Metropolitan. In his biography of Jimmy Renforth, Ian Whitehead complains that ‘He is largely forgotten by the natives of Tyneside...’

I can provide no definite information on who Mr Swaddle or Mr Winship were – though I am sure that this knowledge exists. Certainly in the late 1860s and 1870s there was a well-known oarsman called Thomas Winship, who Ian Whitehead says was from ‘a well-known Tyne rowing family’. Between 1869 and 1871 he was part of the ‘Tyne Champion Four’ with Jimmy Renforth, James Taylor and John Martin. Their most notable victory came in 1870 when defeated the St John, New Brunswick crew, champions of North America, on Lake Lachine in Quebec.

There is a lot of research still to be done (particularly by reference to local newspapers) on the contribution of Swaddle and Winship to rowing in Britain. In fact, Swaddle’s influence went further afield as many of their boats were sold abroad. The Australian Town and Country Journal of 17 September 1880 noted that ‘The cost of a Swaddle and Winship wager boat delivered in Sydney, would be about £30’ (as the boat cost £18, the cost of delivery from Newcastle to Sydney was, presumably, £12). This information comes from Trove, a splendid online resource provided by the National Library of Australia consisting of a vast collection of digitised newspapers, books and images. Trove shows that Australian papers had many references to Swaddle’s boats taking part in numerous races in Australia (and in England) between 1876 and 1889. It was not just singles that were imported, in 1882 Melbourne Rowing Club had an eight sent over. These were their ‘glory years’ when the name of ‘Swaddle and Winship’ was respected not only on the Tyne and on the Thames but also on the Parramatta and the Yarra and, no doubt, on many other famous (and not so famous) courses throughout the rowing world.

Another typical race over the Tyne Championship Course. On 3 April 1882, Ned Hanlan (in a Phelps and Peters boat) beat R.W. Boyd (in a Swaddle and Winship boat) for the titles of both World and English Sculling Champion – and for a £1,000 prize. To get an idea of what this was worth, Ian Whitehead says that in 1870 an unskilled man would earn £1 a week and a skilled man £1.50. Thus, £1,000 could mean ten years pay for twenty minutes work.

*Bonny - a term used by people from the Tyneside region of North East England meaning ‘beautiful’.

** Notable exceptions are Harry Clasper: Hero of the North (1990) and Rowing: A Way Of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside (2003) by David Clasper, The Sporting Tyne: A History of Professional Rowing (2002) and James Renforth Champion Sculler of the World (2004) by Ian Whitehead, The Tyne Oarsmen: Harry Clasper, Robert Chambers, James Renforth (1993) by Peter Dillon. Chris Dodd is currently producing a work on Tyne rowing.

Tim Koch writes:

A recent HTBS posting asked about Swaddle and Winship boat builders, a Newcastle-on-Tyne firm which built much admired racing boats in the 1870s and 1880s. I cannot produce anything like the full story of the firm, but I can provide some background to their work plus some (fairly random) aspects of their history.

Newcastle’s High Level Bridge on the River Tyne, the starting point for many famous professional sculling races.

To the casual observer of British rowing history, it would be easy to get the idea that very little has happened beyond Putney and Henley or Oxford and Cambridge and I am probably one of those who are guilty of promulgating this idea. I cannot correct this is in one posting but it is true that Newcastle-on-Tyne, an industrial city in the North East of England born of mining and ship building, has made a very large contribution to the sport of rowing and to the art (or science) of boat building. By the mid-nineteenth century, rowing on the River Tyne was a massive spectator sport among ordinary working people and a lot of money was changing hands through betting. Many improvements in boat design and in rowing technique came out of Newcastle, most famously from its three favourite sons, Robert Chambers, James Renforth and, in particular, Harry Clasper.

An early painting of Harry Clasper. Rather like the painting of another Newcastle sculler, Edward Hawkes, this picture appears to have had Clasper’s head added at a later date. The depiction of the boat cannot be taken as entirely accurate either.

Professional scullers were the first sporting heroes of the industrial working class (long before soccer players took this role). These oarsmen were not the ‘gentlemen amateurs’ of London and the south, they were tough working men who needed their boats to go fast so they could make the big money that gambling brings. Then as now, for many people with a less than privileged start in life, success in sport or show business was the only conceivable way to improve their lot. For this reason (and unlike many of the conservative amateur oarsmen) professionals produced or readily adopted new innovations such as outriggers, carvel hulls, sliding seats, swivel rowlocks, overlapping handles and keel fins and adapted their rowing styles to fit the new equipment. Further, it is mostly forgotten that for a long time England had two famous ‘Championship Courses’ for boat racing. One was the 4-mile, 374-yard Putney to Mortlake course on the Thames and the other was the 3-mile, 570-yard High Level Bridge to the Scotswood Suspension Bridge course on the Tyne.

This illustration records a race typical of the calibre of those that took place on the Tyne Championship Course. After one of the greatest and most innovative of all scullers, Ned Hanlan, had become champion of Canada in 1877 and of the United States in 1878, he travelled to Britain in 1879 to take on the best the country could offer. The venue for his race against the English champion, William Elliott, was not on the Thames but was on the Tyne, before a crowd of 10,000. The Englishman used a Swaddle and Winship and Hanlan took two of the company’s boats back to the United States. The top picture shows the start at the High Level Bridge and the lower picture shows the finish at the Scotswood Suspension Bridge.

It should be of no surprise therefore that Newcastle should produce a highly respected firm of boat builders such as Swaddle and Winship. Rowing historian Eric Halladay held that by 1880 the three most important boat builders were John Hawks Clasper (a Newcastle man based in Putney), Sims of Putney and Swaddle and Winship of Scotswood, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

From references in The Times it seems that the Cambridge Boat Race crew used Swaddle’s boats from 1876 to 1883 and Oxford from 1878 to 1882. The firm’s ‘big break’ came in the 1876 University Boat Race when they built the winning craft. The quote below is from The Australian Town and Country Journal of 27 May 1876 (they may have taken it verbatim from a British publication such as Bell’s Life):

Cambridge (use) the new boat built for them by Swaddle and Winship, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, it having developed better qualities than their Searle boat... she is considerably lighter than their Searle... A novelty about the new ship is a somewhat peculiar arrangement of the ‘riggers,’ which dispenses with a consolable amount of the supporting woodwork and, as far as it can go, diminishes her weight... This is the first eight oar ever built in the north – at any rate in modern times – for either University, and should Cambridge win in her this year the firm of Swaddle and Winship is certain to become in great request, just as Clasper made his reputation as a builder by the boat in which Goldie first showed Cambridge the way to victory after a decade of defeat.

At least two of the eights Swaddle and Winship produced for the Boat Race became particularly well known, the Cambridge boat of 1877 and the Oxford boat of 1879.

Rowing historian Chris Dodd says this about the start of the 1877 ‘Dead Heat’ race it in his 1983 book, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race:

...the race started at 8.27am.... There was brilliant sun and a chilling wind, and Oxford had won the toss and chosen Middlesex, and were on the water first. Cambridge had a last minute panic about their Swaddle and Winship (boat). It was a short heavily cambered craft, and..... was very fast in calm water but stuck her nose into the wind if there was one, needing a great deal of rudder. The wind was from the west-northwest, the worst possible for Cambridge, and so they fixed a false keel to the boat at the last moment...

I am currently making a video for HTBS about the 1877 race and recently went to the River and Rowing Museum at Henley to interview Chris. To my delight, he produced what is alleged to be the bows of the boat made by Swaddle and Winship for CUBC in 1877. Unfortunately, it has no provenance beyond what is painted on it. It is illuminated with the names of the Oxford crew on one side and the Cambridge crew on the other. Both sides say ‘Portion of Boat used by Cambridge Crew. Dead heat.’

Allegedly the bow of the Swaddle and Winship boat used by Cambridge in the 1877 Boat Race. The Light Blue crew is recorded on the stroke (port) side....

... and the Dark Blues are on the bow (starboard) side.

As to the Oxford boat of 1879, The Times of 12 March 1884 had a report on a ‘sportsman’s exhibition’ held in London which included a display of racing boats.

The Oxford boat shown has been used in the (Boat Race) since 1879 [actually 1879 to 1882, TK], and is considered to be the best boat the Oxford crew has ever used. This was built by Swaddle and Winship of Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the same firm lent other specimens of boat building which have been used successfully in great races.

The 1879 Boat Race at Hammersmith. Between 1878 and 1882 both crews used Swaddle and Winship boats.

Of course, by implying that approval by the gentlemen amateurs of Oxford and Cambridge was the ultimate accolade, I continue to marginalise rowing outside of the south of England. My only (rather inadequate) defence is that the history of professional and north of England rowing has been sparsely recorded compared to amateur rowing in southern England.** Even successful amateurs from places like Tyneside are little remembered, men like William Fawcus of Tynemouth Rowing Club who won amateur sculling’s ‘Triple Crown’ in 1871 with victories in the Diamonds, Wingfields and Metropolitan. In his biography of Jimmy Renforth, Ian Whitehead complains that ‘He is largely forgotten by the natives of Tyneside...’

I can provide no definite information on who Mr Swaddle or Mr Winship were – though I am sure that this knowledge exists. Certainly in the late 1860s and 1870s there was a well-known oarsman called Thomas Winship, who Ian Whitehead says was from ‘a well-known Tyne rowing family’. Between 1869 and 1871 he was part of the ‘Tyne Champion Four’ with Jimmy Renforth, James Taylor and John Martin. Their most notable victory came in 1870 when defeated the St John, New Brunswick crew, champions of North America, on Lake Lachine in Quebec.

There is a lot of research still to be done (particularly by reference to local newspapers) on the contribution of Swaddle and Winship to rowing in Britain. In fact, Swaddle’s influence went further afield as many of their boats were sold abroad. The Australian Town and Country Journal of 17 September 1880 noted that ‘The cost of a Swaddle and Winship wager boat delivered in Sydney, would be about £30’ (as the boat cost £18, the cost of delivery from Newcastle to Sydney was, presumably, £12). This information comes from Trove, a splendid online resource provided by the National Library of Australia consisting of a vast collection of digitised newspapers, books and images. Trove shows that Australian papers had many references to Swaddle’s boats taking part in numerous races in Australia (and in England) between 1876 and 1889. It was not just singles that were imported, in 1882 Melbourne Rowing Club had an eight sent over. These were their ‘glory years’ when the name of ‘Swaddle and Winship’ was respected not only on the Tyne and on the Thames but also on the Parramatta and the Yarra and, no doubt, on many other famous (and not so famous) courses throughout the rowing world.

Another typical race over the Tyne Championship Course. On 3 April 1882, Ned Hanlan (in a Phelps and Peters boat) beat R.W. Boyd (in a Swaddle and Winship boat) for the titles of both World and English Sculling Champion – and for a £1,000 prize. To get an idea of what this was worth, Ian Whitehead says that in 1870 an unskilled man would earn £1 a week and a skilled man £1.50. Thus, £1,000 could mean ten years pay for twenty minutes work.

*Bonny - a term used by people from the Tyneside region of North East England meaning ‘beautiful’.

** Notable exceptions are Harry Clasper: Hero of the North (1990) and Rowing: A Way Of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside (2003) by David Clasper, The Sporting Tyne: A History of Professional Rowing (2002) and James Renforth Champion Sculler of the World (2004) by Ian Whitehead, The Tyne Oarsmen: Harry Clasper, Robert Chambers, James Renforth (1993) by Peter Dillon. Chris Dodd is currently producing a work on Tyne rowing.

Monday, May 16, 2011

The Putney Embankment – London’s ‘Boathouse Row’, Part 3

Here continues Tim Koch’s third and final part of his story about The Putney Embankment – London’s Boathouse Row.

Vesta RC had been formed in 1871 and was initially based at the Feathers Boathouse on the River Wandle in south London. By 1875 it had moved to the Unity Boat House on the Putney Embankment (run by the famous rowing and boatbuilding Phelps family for many years). The Unity is now Ranelagh Sailing Club, situated between Westminster School BC and the building that Vesta erected as its boathouse in 1890 and which still serves it today.

The only Victorian boathouse not yet mentioned that still stands on the Embankment started life slightly differently. What is now Westminster School Boat Club was erected by the boat builder, J.H. Clasper, I think in the 1880s. John Hawks Clasper (1835-1908) was the son of the famous and innovative Newcastle boat builder, oarsman and coach, Harry Clasper (1812-1870). John moved south in the late 1860s and by the 1870s was building boats in Wandsworth (just upriver from Putney) and in Oxford. Many of the boats used in the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race in this period were made by him. The first reference that I have of him as ‘Clasper of Putney’ is 1882 when he ‘steered’ Payne in the Wingfield Sculls from a following boat. Between 1887 and 1897, ‘Clasper of Putney’ again built many of the craft used in the University Boat Race. The original building has been thoughtfully and ‘lightly’ adapted for modern use by WSBC and the name ‘JH Clasper’ is still nicely picked out in red brick on the gable end (see above and on top).

The next surviving boathouse at Putney dates from much later. It is the very pleasing building put up for Imperial College (London) BC in 1937. The PECA Report again:

‘Its sleek moderne lines make for an attractive contrast to the dominant Victoriana, varying the styles of the group of boathouses but keeping to their overall character. It is a highly individual and positive building, featuring a wave motif on the rendered panel beneath its cluster of Crittall windows. It is also one of the only quintessentially 1930s buildings in this part of Putney. A contemporary extension to the boat house […] was added in 1997.’

The modern extension is not unattractive and it allows the original and better part of the boathouse to dominate. Sadly, a small terrace of Victorian houses had to be demolished to make way for it.

The remaining architectural ‘style’ on the Embankment is, unfortunately, that of the post 1939-1945 War period. The PECA is generous:

‘[…] relatively recent additions reflect the architecture style of the 50s and 60s and should be regarded as positive in terms of their function and group value even though their overall design lacks the finesse of their neighbours.’

While accepting that a rowing club must be a functional place and not (in the words of the late Peter Coni) ‘a sporting slum’, I find it hard to be positive about the architecture of Kings College School (built for Barclays Bank RC), HSBC (since 1992 the name for the Midland Bank, the full name of the ‘Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation’ is never used) and Dulwich College (built for the NatWest Bank RC). The only building with some character in this group is that of Crabtree BC (built for Lensbury RC, a club for Shell Oil and British Petroleum employees). I find it difficult to date but its nice external spiral staircase suggests that it may be older than its three neighbours to the west.

In its conclusions, the Putney Embankment Conservation Area Report says:

‘Many of the boathouses on the Embankment are fine or indeed excellent buildings, but it is their use that gives them their group character.’

That ‘use’ is rowing. Long may it continue!

The Putney Embankment – London’s ‘Boathouse Row’, Part 1.

The Putney Embankment – London’s ‘Boathouse Row’, Part 2.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)