Just like Tim Koch sometimes gets inspired to write a blog post after having read something on HTBS, so do I. Tim’s entry on Monday 27 January, about the Blues’ baggy trousers, ‘Oxford Bags’, made my think of the opposite one could say, ‘rowing shorts’. (As a matter of fact, I was reading about Stanley ‘Muttle’ Muttlebury and came across a quotation by Rudie Lehmann, who wrote about Muttle’s shorts; more about that later in this post.)

Allow me to first make a couple of general statements: short trousers/pants, knee-pants, Knickerbockers, shorts, and whatever you would like to call them, were, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, clothing for boys: think school uniforms, boy scouts, and more boyish activities. However, in certain sports grown men were seen wearing this garment, for example oarsmen when they were rowing. Besides this athletic activity and a few others, it was first after the Second World War, where soldiers fighting in the tropics had had shorts to go with their uniforms, that shorts became generally accepted as a sport garment for a gentleman, or when he went on holiday to a beach resort.

Of course, nowadays there are other rules for men in shorts: if you are not sure what these rules are, read what the magazine The Tatler says about them, here, and the website Art of Manliness says, here. (Other websites will also give you homo-erotic explanations of men in shorts, but that is beyond the point of this article.)

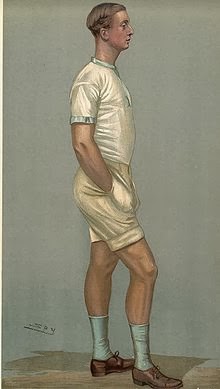

Without really trying to be scientific, I took a look at the cartoons of oarsmen who have been depicted in the magazine Vanity Fair, which was first published in 1868. Nearly 25%, or twelve out of the 50 rowers (or were there 59 oarsmen altogether?), who were depicted between 1889 and 1912 in Vanity Fair are showing ‘legs’ (the first oarsman who was caricatured, Sir Stafford Northcote, appeared in the magazine in October 1870). First out in shorts in Vanity Fair was the Henley Royal Regatta legend, Guy Nickalls, who showed up in his rowing kit on 20 July 1889 in the magazine.

Second man out, in shorts in Vanity Fair, was the great Cambridge oarsman, Stanley Duff ‘Muttle’ Muttlebury (in Vanity Fair on 22 March 1890), who, as a matter of fact, is the only oarsman out of the 50 who is depicted holding an oar in a boat. (Robert Henry Foster – 6 July 1910 – is not wearing shorts, nor is he sitting in a boat, but there is at least an eight in the background behind him in his Vanity Fair cartoon). Rudie Lehmann, who showed up in Tim’s blog post wearing ‘Oxford Bags’, wrote about Muttle and his short shorts in verse:

Muttle at six is ‘stylish’, so at least The Field reports;

No man has ever worn, I trow, so short a pair of shorts.

His blade sweeps through the water, as he swings his 13.10,

And pulls it all, and more than all, that brawny king of men.

A year after, almost on the day, Muttle had had his 13 st. 10 lbs. shown in Vanity Fair, Guy Nickalls’s best friend and rowing partner Oliver Arthur Villers Russell, more known as Lord Ampthill, was depicted in Vanity Fair (21 March 1891) showing a stylish fashion, (Oxford) blue jacket and rowing cap, tan shorts and brown knee socks and brown shoes.

Then it took some years before another oarsman showed up, exposing some legs in Vanity Fair, Hugh Benjamin ‘Benjie’ Cotton (15 March 1894), who was a fairly short and light oarsman, who also rowed successfully in the colours of the Dark Blues, which was shown by the oar he was holding in his right hand. Cotton, too, was wearing brown knee socks and brown shoes.

Charles Murray Pitman (28 March 1895) was said to have been ‘a cheerful, wholesome boy, full of pluck’, but lazy outside the boat, though in the boat, he won four successive Boat Races for Oxford, in 1892-1895.

Then there was Walter Eskine 'Crumbo' Crum (19 March 1896), who in Vanity Fair was called ‘quite a fine specimen of young English manhood’ by the artist ‘SPY’, who, however, did not mention anything about the oarsman’s knees or legs, but did write that ‘his chief peculiarities are a beautiful complexion, an almost girlish look, a very frequent blush (which is the outcome of much modesty)’. Crumbo is also, just as Lord Ampthill, wearing a blue blazer with a white pocket square, brown knee socks and white shoes and cap in hand. He looks very dashing.

The legendary oarsman and coach Harcourt Gilbey ‘Tarka’ Gold (23 March 1899) was the first man to be knighted for his services to the sport of rowing, and also the first man who received a comment from ‘SPY’ about his knees in Vanity Fair. SPY wrote: ‘He has wonderful knees; and his legs are always loudly appreciated by the crowd at Putney.’ I leave it to you readers to decide if Tarka’s knees are more ‘wonderful’ than, say ‘Duggie’ Stuart’s or ‘Ethel’ Etherington-Smith’s?

William Dudley-Ward (29 March 1900) met with great opposition within the own ranks when he, as the president of Cambridge University Boat Club, for the 1898 Boat Race, brought in the famous Oxford oarsman and coach William Fletcher to coach the Light Blues. The Dark Blues had been victorious for eight consecutive years so it was a question of finding an answer to the problem with some kind of a 'desperate-times-call-for-desperate-measures' solution. However, the crew was struck with misfortune. Getting close to Boat Race Day, the stroke Charles Steele went down with influenza and could not row and President Dudley-Ward was ordered by his doctor not to row. Second seated, Adam Bell, the 'old man' in the crew, moved reluctantly to the stroke seat. Oxford won the race. The following year, Cambridge won, stopping the Dark Blues to get their tenth straight victory. Then, two days after Dudley-Ward - now president of Cambridge University BC again - was depicted in Vanity Fair, on 31 March 1900, Cambridge won, now with twenty boat lengths. In the Vanity Fair print Dudley-Ward is seen with his turned-upped/cuffed shorts and Cambridge-blue socks.

Wilfrid Hubert Chapman (2 April 1903) rowed in the Eton crews that won the Ladies’ Plate at Henley in 1897 and 1898. He was to row bow in the Light Blues’ crew of 1899, but decided not to participate. In February 1900, as Second Lieutenant at the Sixth Yorkshire Regiment, Chapman went to fight in South Africa, but was sent home with fever the next year, in March. He then rowed in the winning Cambridge crews in the 1902 and 1903 Boat Races. It was said that Chapman ‘was probably the most dashing bow who ever rowed in that place’, which referred to his rowing style, as he was ‘not particular about dress’. At the outbreak of the First World War, he left his job at Bombay Company in Karachi to rejoin the Sixth Yorkshire Regiment. Captain Chapman was one of the first ones to get killed at the landing at Suvla Bay in the Dardanelles – the only oarsman depicted in Vanity Fair killed in action during the First World War.

About Raymond Broadley 'Ethel' Etherington-Smith, SPY wrote that he was 'the finest and handsomest young athlete I ever drew as an under-graduate', but by summer 1908, the oarsman, in the picture seen in his Leander kit, was 31 years old and a newly Olympic gold medallist in the eights. The Leander crew had been hand-picked by coach Tarka Gold to form the British 'B crew' at the Olympic regatta in Henley-on-Thames. Compared to the British first selected boat, the 1908 Cambridge winning crew in the Boat Race that year, which had been stroked by Duggie Stuart, the Leander crew were older rowers, going by the name of the 'Old Crocks'. Other oarsmen in the 'Old Crocks' crew, who had been depicted in Vanity Fair, were Banner 'Bush' Johnstone and Guy Nickalls. In September 2012, Ethel's 1908 Olympic gold medal was sold for an astonishing £17,500 ($27,738).

That was the twelve oarsmen in Vanity Fair wearing shorts in the magazine. We have to save the oarsmen and oarswomen wearing lycra/spandex till another time.

Much of the information about the Vanity Fair oarsmen was collected from the brilliant "Rowers of Vanity Fair" on Wikipedia.