Friday, February 28, 2014

Rudie Lehmann's Harvard Honorary Degree

While the famous coach and writer on rowing matters, Rudie Lehmann is mostly remembered for coaching either Oxford or Cambridge (he studied and rowed for Cambridge, but never in a Blue boat), Lehmann also coached Berliner Ruder Klub and Harvard University.

He received an invitation in 1896 from his American friend Francis Peabody, whom he had rowed with at Cambridge. The rowing at Harvard University was in disorder so Lehmann was offered the opportunity to give Harvard a helping hand, teaching the crimson crews the proper English stroke. Lehmann arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for the first time in mid-November 1896. He returned to Harvard both in 1897 and 1898, and although Harvard greatly improved with Lehmann as their coach, the crimsons never won a race during this time.

As the true gentleman coach, Lehmann never asked for any pay. In June 1897, Harvard awarded Lehmann an honorary degree, which was reported in some American newspapers. With the head line "Mr. Lehmann Speaks at the Harvard Commencement Dinner" the Cornell Daily Sun wrote on 2 July 1897:

It is said that all records for enthusiasm at a Harvard commencement dinner were broken when Mr. R. C. Lehmann was called upon for the third toast. Mr. Lehmann spoke as follows:

“It is my duty to-day to endeavor to the best of my ability to pay the many debts that I have incurred since I came among you in the early spring, but in the first place let me discharge, so far as I can, one debt of gratitude. I mean the debt I owe to this great university, and the high distinction which she has to-day conferred upon me by giving me an honorary degree. [Applause.] Whereas formerly it was my feeling that I might look on as a stranger, a sympathizing stranger only, now I feel that it is my right to cherish the great traditions that have come down to the university through the past generations; that it is my duty to take an active and deep interest in all that concerns her welfare, looking back on all that has passed since the first little seed was planted at Harvard. Looking back to all that has passed, I cannot tell you how deeply I feel the honor that has been done me today in making me one of the great body of Harvard graduates. [Applause.]

“Secondly, I desire to acknowledge the kindliness and consideration, the courtesy and generosity that have been extended to me ever since I set foot on these shores by every man connected with the university, from President Eliot down.

“For your President found time in the midst of all his engrossing duties – he found time, I say – to express his interest in the crew, and to show that whatever went on in Harvard, whether it was a matter of academic or athletic exercise, it was a matter of the deepest concern to him. [Applause]

“For that expression which he gave l thank him. I can assure him that when it was communicated to the crew it touched their hearts deeply.

“I cannot help thinking on this occasion of what might have been. [Applause] I might have represented here a victorious cause, but the dream has passed for this year at any rate.

“Coming among you, as I have to-day, I have found that Harvard men are always ready and willing to extend a greeting, even though they have met with defeat. I have seen to-day men whose friendship it has been my privilege to make, and as I clasped their hands and look into their eyes no words were necessary to assure me how deeply they as Harvard men felt for what happened on Friday last.

“I have seen also men whom I scarcely knew by name, who have come to me and expressed their empathy and their hope that on some future day Harvard might yet win in a boat race.

“I assure you, gentlemen, that this expression of kindliness has overwhelmed me.

“It is the custom to look upon us Englishmen as a sort of coldblooded and phlegmatic race, and in many respects we are; but I think when you once touch us, when you pierce through that outer crust of reserve, you will find we are stirred by emotion as high, by enthusiasm as sincere, and by a generosity not less deep than the qualities you find in the men at Harvard.

“At any rate, it is in the spirit of one who has been adopted as your brother that I appear here before you, and I feel, having been associated with one of her athletic interests, that I have become a son of Harvard and a brother to those whom I see around me, united with them in a spirit and devotion which I hope will last as long life itself.” |Applause.]

Lehmann showing the stroke in a fixed-seat.

So what did Rudie Lehmann get out of his time in America, more than an honorary degree at Harvard? Well, on 14 September 1898, a short piece in The New York Times informed that Harvard’s English coach the previous day had married Miss Alice Marie Davis in Worcester, Massachusetts. Lehmann had met Miss Davis in Mr. and Mrs. Francis Peabody’s home, where she gave the Peabodys’ daughters tutorials.

On the day of the article, the 42-year-old Englishman sailed with his 24-year-old American bride aboard Majestic to Liverpool, England. ‘On arriving home to their house, "Fieldhead", at Bourne End, they were greeted with a triumphal arch, a banquet in the village and an address from the vicar’ the American rowing historian Thomas Mendenhall wrote in a 1979 article about Rudie Lehmann.

He received an invitation in 1896 from his American friend Francis Peabody, whom he had rowed with at Cambridge. The rowing at Harvard University was in disorder so Lehmann was offered the opportunity to give Harvard a helping hand, teaching the crimson crews the proper English stroke. Lehmann arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for the first time in mid-November 1896. He returned to Harvard both in 1897 and 1898, and although Harvard greatly improved with Lehmann as their coach, the crimsons never won a race during this time.

As the true gentleman coach, Lehmann never asked for any pay. In June 1897, Harvard awarded Lehmann an honorary degree, which was reported in some American newspapers. With the head line "Mr. Lehmann Speaks at the Harvard Commencement Dinner" the Cornell Daily Sun wrote on 2 July 1897:

It is said that all records for enthusiasm at a Harvard commencement dinner were broken when Mr. R. C. Lehmann was called upon for the third toast. Mr. Lehmann spoke as follows:

“It is my duty to-day to endeavor to the best of my ability to pay the many debts that I have incurred since I came among you in the early spring, but in the first place let me discharge, so far as I can, one debt of gratitude. I mean the debt I owe to this great university, and the high distinction which she has to-day conferred upon me by giving me an honorary degree. [Applause.] Whereas formerly it was my feeling that I might look on as a stranger, a sympathizing stranger only, now I feel that it is my right to cherish the great traditions that have come down to the university through the past generations; that it is my duty to take an active and deep interest in all that concerns her welfare, looking back on all that has passed since the first little seed was planted at Harvard. Looking back to all that has passed, I cannot tell you how deeply I feel the honor that has been done me today in making me one of the great body of Harvard graduates. [Applause.]

“Secondly, I desire to acknowledge the kindliness and consideration, the courtesy and generosity that have been extended to me ever since I set foot on these shores by every man connected with the university, from President Eliot down.

“For your President found time in the midst of all his engrossing duties – he found time, I say – to express his interest in the crew, and to show that whatever went on in Harvard, whether it was a matter of academic or athletic exercise, it was a matter of the deepest concern to him. [Applause]

“For that expression which he gave l thank him. I can assure him that when it was communicated to the crew it touched their hearts deeply.

“I cannot help thinking on this occasion of what might have been. [Applause] I might have represented here a victorious cause, but the dream has passed for this year at any rate.

“Coming among you, as I have to-day, I have found that Harvard men are always ready and willing to extend a greeting, even though they have met with defeat. I have seen to-day men whose friendship it has been my privilege to make, and as I clasped their hands and look into their eyes no words were necessary to assure me how deeply they as Harvard men felt for what happened on Friday last.

“I have seen also men whom I scarcely knew by name, who have come to me and expressed their empathy and their hope that on some future day Harvard might yet win in a boat race.

“I assure you, gentlemen, that this expression of kindliness has overwhelmed me.

“It is the custom to look upon us Englishmen as a sort of coldblooded and phlegmatic race, and in many respects we are; but I think when you once touch us, when you pierce through that outer crust of reserve, you will find we are stirred by emotion as high, by enthusiasm as sincere, and by a generosity not less deep than the qualities you find in the men at Harvard.

“At any rate, it is in the spirit of one who has been adopted as your brother that I appear here before you, and I feel, having been associated with one of her athletic interests, that I have become a son of Harvard and a brother to those whom I see around me, united with them in a spirit and devotion which I hope will last as long life itself.” |Applause.]

Lehmann showing the stroke in a fixed-seat.

So what did Rudie Lehmann get out of his time in America, more than an honorary degree at Harvard? Well, on 14 September 1898, a short piece in The New York Times informed that Harvard’s English coach the previous day had married Miss Alice Marie Davis in Worcester, Massachusetts. Lehmann had met Miss Davis in Mr. and Mrs. Francis Peabody’s home, where she gave the Peabodys’ daughters tutorials.

On the day of the article, the 42-year-old Englishman sailed with his 24-year-old American bride aboard Majestic to Liverpool, England. ‘On arriving home to their house, "Fieldhead", at Bourne End, they were greeted with a triumphal arch, a banquet in the village and an address from the vicar’ the American rowing historian Thomas Mendenhall wrote in a 1979 article about Rudie Lehmann.

Thursday, February 27, 2014

Sharing History about Swaddle and Winship

During January and February, we have had two articles posted on HTBS about the boatbuilding company Swaddle and Winship (see 13 January and 24 February). The writing actually began when HTBS received an e-mail with some questions from a lady, Mrs. Paula, who lives in the north of England. She is the great-great-granddaughter of boatbuilder George Swaddle and great-great-great-granddaughter of boatbuilder Thomas Swaddle.

She wrote that she has always known that her Swaddle ancestors were boatbuilders on the River Tyne in Newcastle, but it was first recently she discovered that the boats they built were racing shells. Paula writes, ‘I was amazed to find their boats were used in the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Races, and also exported all over the world! I had no idea. Now I am fascinated to find out more.’

While both Tim Koch and I could fill in some holes and help Paula with information about her famous ancestors, she already had gathered some interesting information about Swaddle and Winship. With her blessing, HTBS can here give you access to some of her finds. Slightly edited, Paula writes:

‘I do now know who Mr. Swaddle and Mr. Winship were in ‘Swaddle and Winship’. It was Thomas Swaddle (approx. 1831 to 1895) and William Winship. As far as I can ascertain, Thomas Swaddle progressed from carpentry to boatbuilding in the 1860s. I don’t know exactly when he teamed up with William Winship, but by 1876 they were a team. William Winship appears to have been a younger man and I think was a sportsman himself (the Thomas Winship Mr. Koch mentions must surely be a relative of William though I don’t know the relationship).

One in the Winship family, Edward Winship was a professional oarsman who rowed in the beginning of the1860s in the Harry Clasper's crew. (Picture from David Clasper's book Rowing: A Way of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside; 2003.)

‘As Mr. Koch says, the Swaddle and Winship company heyday was from approx. 1876 to 1882. In Decmber 1882 the company went bankrupt. However, boatbuilding continued on the Tyne under the Swaddle name. It appears (evidence somewhat circumstantial) that Thomas Swaddle stayed on the Tyne building boats until his death in 1895, but, due to the bankruptcy, the business would probably have been in his eldest son’s hands (?). His eldest son was George Swaddle (1851 to 1924). By the 1890s, George Swaddle and William Winship were building boats on the Thames (again I presume under the Swaddle name as William Winship was bankrupt). When Thomas Swaddle died in 1895, it appears his youngest son William Swaddle took over the Swaddle boatbuilding business on the Tyne (as his eldest son George was building boats on the Thames at that point). Unfortunately, William Swaddle died relatively young in 1903. What happened to the Swaddle boatbuilding business on the Tyne after that I don’t yet know. George Swaddle did return to Tyneside sometime after 1911. The Swaddle boatyard, with its name on, was apparently still visible at Scotswood in the 1930s, but I guess no longer as a going concern.’

Many warm thanks to Paula for sharing this information about her ancestors.

The photograph of the wooden single scull was taken by the HTBS editor in the summer of 2002 at the WoodenBoat Show in Rockland, Maine (USA). The plaque in the shell said that it was built by ‘Swaddle & Co.’, probably in the 1860s.

|

| Swaddle & Co. |

While both Tim Koch and I could fill in some holes and help Paula with information about her famous ancestors, she already had gathered some interesting information about Swaddle and Winship. With her blessing, HTBS can here give you access to some of her finds. Slightly edited, Paula writes:

‘I do now know who Mr. Swaddle and Mr. Winship were in ‘Swaddle and Winship’. It was Thomas Swaddle (approx. 1831 to 1895) and William Winship. As far as I can ascertain, Thomas Swaddle progressed from carpentry to boatbuilding in the 1860s. I don’t know exactly when he teamed up with William Winship, but by 1876 they were a team. William Winship appears to have been a younger man and I think was a sportsman himself (the Thomas Winship Mr. Koch mentions must surely be a relative of William though I don’t know the relationship).

One in the Winship family, Edward Winship was a professional oarsman who rowed in the beginning of the1860s in the Harry Clasper's crew. (Picture from David Clasper's book Rowing: A Way of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside; 2003.)

‘As Mr. Koch says, the Swaddle and Winship company heyday was from approx. 1876 to 1882. In Decmber 1882 the company went bankrupt. However, boatbuilding continued on the Tyne under the Swaddle name. It appears (evidence somewhat circumstantial) that Thomas Swaddle stayed on the Tyne building boats until his death in 1895, but, due to the bankruptcy, the business would probably have been in his eldest son’s hands (?). His eldest son was George Swaddle (1851 to 1924). By the 1890s, George Swaddle and William Winship were building boats on the Thames (again I presume under the Swaddle name as William Winship was bankrupt). When Thomas Swaddle died in 1895, it appears his youngest son William Swaddle took over the Swaddle boatbuilding business on the Tyne (as his eldest son George was building boats on the Thames at that point). Unfortunately, William Swaddle died relatively young in 1903. What happened to the Swaddle boatbuilding business on the Tyne after that I don’t yet know. George Swaddle did return to Tyneside sometime after 1911. The Swaddle boatyard, with its name on, was apparently still visible at Scotswood in the 1930s, but I guess no longer as a going concern.’

Many warm thanks to Paula for sharing this information about her ancestors.

The photograph of the wooden single scull was taken by the HTBS editor in the summer of 2002 at the WoodenBoat Show in Rockland, Maine (USA). The plaque in the shell said that it was built by ‘Swaddle & Co.’, probably in the 1860s.

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

More on the 1944 Boat Race

The 1944 Cambridge crew goes out to the start. Photo: “Diamond44” website.

Here on HTBS we are not really done with the 1944 boat race between Oxford and Cambridge, which was held on the River Great Ouse and which we wrote about in a post yesterday, 70-Year Anniversary of an Unofficial Boat Race.

HTBS’s Greg Denieffe wrote in a Comment on yesterday’s post about a film made by a group called The Diamond44. Greg writes, ‘“Diamond44” was set up in 2002 by Terry Overall and was (and still is) dedicated to celebrating and documenting the 1944 University Boat Race and to organising a re-enactment of the 1944 race in February 2004 on The River Great Ouse.’

There are some interesting information on this project’s website, showing photographs both from 1944 and 2004, a short film from the 1944 race, etc. Go to the website here.

HTBS’s ‘other man’ across the pond, Tim Koch, dived into British Pathe’s film archives and found three films from the ‘unofficial boat races’ in 1940 at Henley-on-Thames, 1944 on Great Ouse and 1945 at Henley-on-Thames. Enjoy the films below:

Here on HTBS we are not really done with the 1944 boat race between Oxford and Cambridge, which was held on the River Great Ouse and which we wrote about in a post yesterday, 70-Year Anniversary of an Unofficial Boat Race.

HTBS’s Greg Denieffe wrote in a Comment on yesterday’s post about a film made by a group called The Diamond44. Greg writes, ‘“Diamond44” was set up in 2002 by Terry Overall and was (and still is) dedicated to celebrating and documenting the 1944 University Boat Race and to organising a re-enactment of the 1944 race in February 2004 on The River Great Ouse.’

There are some interesting information on this project’s website, showing photographs both from 1944 and 2004, a short film from the 1944 race, etc. Go to the website here.

HTBS’s ‘other man’ across the pond, Tim Koch, dived into British Pathe’s film archives and found three films from the ‘unofficial boat races’ in 1940 at Henley-on-Thames, 1944 on Great Ouse and 1945 at Henley-on-Thames. Enjoy the films below:

OXFORD & CAMBRIDGE BOAT RACE

OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE BOAT RACE

BOAT RACE AT HENLEY

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

70-Year Anniversary of an Unofficial Boat Race

The Oxford University Boat Club is just to launch their eight on the River Great Ouse 70 years ago. Photo: Eastern Daily Press.

Last Sunday, the Eastern Daily Press, a newspaper in the Norfolk area in the East of England, published an interesting article about a rowing 70-year anniversary. Then, in 1944, Cambridge and Oxford met in an eight race on the River Great Ouse, close to Ely. In the article, “Anniversary of only Oxford-Cambridge boat race not rowed on River Thames to be commemorated”, the newspaper writes, ‘It was the only time that the race was contested away from London, forced to seek refuge from the “doodlebug” V1 bombs that were raining down on the capital.’

Now, whether you believe me or not, I just hate to be a Besserwisser, but I still feel I have to point out at least two inaccuracies in the article: The first Boat Race between the universities was held in 1829 in Henley-on-Thames, so there was one time the official race was held outside of London. The 1944 boat race on River Great Ouse was one of four unofficial boat races between Oxford and Cambridge held during the Second World War. The first race during the War was in 1940 at Henley-on-Thames, and then followed two years when the universities did not met, while in 1943, they met on Sandford-on-Thames, in 1944 on Great Ouse and for the 1945 race, Oxford and Cambridge raced at Henley-on-Thames again.

These four unofficial boat races are not in the official list of the Boat Race between the universities and none of the oarsmen who competed were awarded Blues. This being said, the boat races during the War years were met with a large interest from the public and the newspapers.

And for the oarsmen who raced during the War, like Martin Whitworth, who was in the four seat in the Cambridge boat, and Michael Brooks, who was in the three seat in the Oxford boat, the 1944 race was the race of their life-time, being awarded Blues, or not. Whitworth and Brooks, now both in their late 80s, will attend the reunion of the 1944 boat race – I tip my cap for both these gentlemen.

Last Sunday, the Eastern Daily Press, a newspaper in the Norfolk area in the East of England, published an interesting article about a rowing 70-year anniversary. Then, in 1944, Cambridge and Oxford met in an eight race on the River Great Ouse, close to Ely. In the article, “Anniversary of only Oxford-Cambridge boat race not rowed on River Thames to be commemorated”, the newspaper writes, ‘It was the only time that the race was contested away from London, forced to seek refuge from the “doodlebug” V1 bombs that were raining down on the capital.’

Now, whether you believe me or not, I just hate to be a Besserwisser, but I still feel I have to point out at least two inaccuracies in the article: The first Boat Race between the universities was held in 1829 in Henley-on-Thames, so there was one time the official race was held outside of London. The 1944 boat race on River Great Ouse was one of four unofficial boat races between Oxford and Cambridge held during the Second World War. The first race during the War was in 1940 at Henley-on-Thames, and then followed two years when the universities did not met, while in 1943, they met on Sandford-on-Thames, in 1944 on Great Ouse and for the 1945 race, Oxford and Cambridge raced at Henley-on-Thames again.

These four unofficial boat races are not in the official list of the Boat Race between the universities and none of the oarsmen who competed were awarded Blues. This being said, the boat races during the War years were met with a large interest from the public and the newspapers.

And for the oarsmen who raced during the War, like Martin Whitworth, who was in the four seat in the Cambridge boat, and Michael Brooks, who was in the three seat in the Oxford boat, the 1944 race was the race of their life-time, being awarded Blues, or not. Whitworth and Brooks, now both in their late 80s, will attend the reunion of the 1944 boat race – I tip my cap for both these gentlemen.

Monday, February 24, 2014

The Bonny* Boats of Newcastle

The Tyne God, the symbol of the River Tyne. A carving of such appears on a wall of Tyne Rowing Club in Newburn, near Newcastle.

Tim Koch writes:

A recent HTBS posting asked about Swaddle and Winship boat builders, a Newcastle-on-Tyne firm which built much admired racing boats in the 1870s and 1880s. I cannot produce anything like the full story of the firm, but I can provide some background to their work plus some (fairly random) aspects of their history.

Newcastle’s High Level Bridge on the River Tyne, the starting point for many famous professional sculling races.

To the casual observer of British rowing history, it would be easy to get the idea that very little has happened beyond Putney and Henley or Oxford and Cambridge and I am probably one of those who are guilty of promulgating this idea. I cannot correct this is in one posting but it is true that Newcastle-on-Tyne, an industrial city in the North East of England born of mining and ship building, has made a very large contribution to the sport of rowing and to the art (or science) of boat building. By the mid-nineteenth century, rowing on the River Tyne was a massive spectator sport among ordinary working people and a lot of money was changing hands through betting. Many improvements in boat design and in rowing technique came out of Newcastle, most famously from its three favourite sons, Robert Chambers, James Renforth and, in particular, Harry Clasper.

An early painting of Harry Clasper. Rather like the painting of another Newcastle sculler, Edward Hawkes, this picture appears to have had Clasper’s head added at a later date. The depiction of the boat cannot be taken as entirely accurate either.

Professional scullers were the first sporting heroes of the industrial working class (long before soccer players took this role). These oarsmen were not the ‘gentlemen amateurs’ of London and the south, they were tough working men who needed their boats to go fast so they could make the big money that gambling brings. Then as now, for many people with a less than privileged start in life, success in sport or show business was the only conceivable way to improve their lot. For this reason (and unlike many of the conservative amateur oarsmen) professionals produced or readily adopted new innovations such as outriggers, carvel hulls, sliding seats, swivel rowlocks, overlapping handles and keel fins and adapted their rowing styles to fit the new equipment. Further, it is mostly forgotten that for a long time England had two famous ‘Championship Courses’ for boat racing. One was the 4-mile, 374-yard Putney to Mortlake course on the Thames and the other was the 3-mile, 570-yard High Level Bridge to the Scotswood Suspension Bridge course on the Tyne.

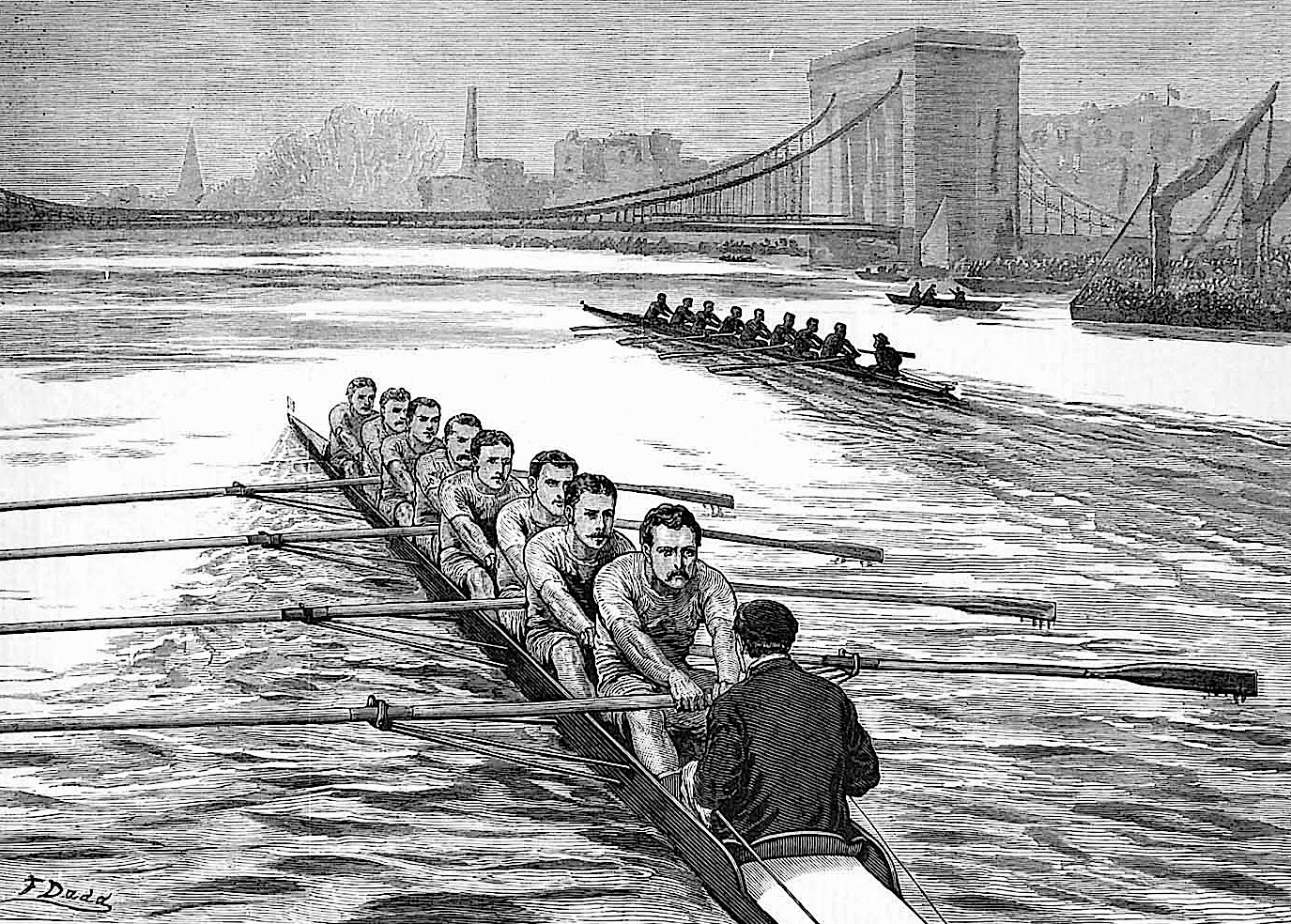

This illustration records a race typical of the calibre of those that took place on the Tyne Championship Course. After one of the greatest and most innovative of all scullers, Ned Hanlan, had become champion of Canada in 1877 and of the United States in 1878, he travelled to Britain in 1879 to take on the best the country could offer. The venue for his race against the English champion, William Elliott, was not on the Thames but was on the Tyne, before a crowd of 10,000. The Englishman used a Swaddle and Winship and Hanlan took two of the company’s boats back to the United States. The top picture shows the start at the High Level Bridge and the lower picture shows the finish at the Scotswood Suspension Bridge.

It should be of no surprise therefore that Newcastle should produce a highly respected firm of boat builders such as Swaddle and Winship. Rowing historian Eric Halladay held that by 1880 the three most important boat builders were John Hawks Clasper (a Newcastle man based in Putney), Sims of Putney and Swaddle and Winship of Scotswood, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

From references in The Times it seems that the Cambridge Boat Race crew used Swaddle’s boats from 1876 to 1883 and Oxford from 1878 to 1882. The firm’s ‘big break’ came in the 1876 University Boat Race when they built the winning craft. The quote below is from The Australian Town and Country Journal of 27 May 1876 (they may have taken it verbatim from a British publication such as Bell’s Life):

Cambridge (use) the new boat built for them by Swaddle and Winship, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, it having developed better qualities than their Searle boat... she is considerably lighter than their Searle... A novelty about the new ship is a somewhat peculiar arrangement of the ‘riggers,’ which dispenses with a consolable amount of the supporting woodwork and, as far as it can go, diminishes her weight... This is the first eight oar ever built in the north – at any rate in modern times – for either University, and should Cambridge win in her this year the firm of Swaddle and Winship is certain to become in great request, just as Clasper made his reputation as a builder by the boat in which Goldie first showed Cambridge the way to victory after a decade of defeat.

At least two of the eights Swaddle and Winship produced for the Boat Race became particularly well known, the Cambridge boat of 1877 and the Oxford boat of 1879.

Rowing historian Chris Dodd says this about the start of the 1877 ‘Dead Heat’ race it in his 1983 book, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race:

...the race started at 8.27am.... There was brilliant sun and a chilling wind, and Oxford had won the toss and chosen Middlesex, and were on the water first. Cambridge had a last minute panic about their Swaddle and Winship (boat). It was a short heavily cambered craft, and..... was very fast in calm water but stuck her nose into the wind if there was one, needing a great deal of rudder. The wind was from the west-northwest, the worst possible for Cambridge, and so they fixed a false keel to the boat at the last moment...

I am currently making a video for HTBS about the 1877 race and recently went to the River and Rowing Museum at Henley to interview Chris. To my delight, he produced what is alleged to be the bows of the boat made by Swaddle and Winship for CUBC in 1877. Unfortunately, it has no provenance beyond what is painted on it. It is illuminated with the names of the Oxford crew on one side and the Cambridge crew on the other. Both sides say ‘Portion of Boat used by Cambridge Crew. Dead heat.’

Allegedly the bow of the Swaddle and Winship boat used by Cambridge in the 1877 Boat Race. The Light Blue crew is recorded on the stroke (port) side....

... and the Dark Blues are on the bow (starboard) side.

As to the Oxford boat of 1879, The Times of 12 March 1884 had a report on a ‘sportsman’s exhibition’ held in London which included a display of racing boats.

The Oxford boat shown has been used in the (Boat Race) since 1879 [actually 1879 to 1882, TK], and is considered to be the best boat the Oxford crew has ever used. This was built by Swaddle and Winship of Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the same firm lent other specimens of boat building which have been used successfully in great races.

The 1879 Boat Race at Hammersmith. Between 1878 and 1882 both crews used Swaddle and Winship boats.

Of course, by implying that approval by the gentlemen amateurs of Oxford and Cambridge was the ultimate accolade, I continue to marginalise rowing outside of the south of England. My only (rather inadequate) defence is that the history of professional and north of England rowing has been sparsely recorded compared to amateur rowing in southern England.** Even successful amateurs from places like Tyneside are little remembered, men like William Fawcus of Tynemouth Rowing Club who won amateur sculling’s ‘Triple Crown’ in 1871 with victories in the Diamonds, Wingfields and Metropolitan. In his biography of Jimmy Renforth, Ian Whitehead complains that ‘He is largely forgotten by the natives of Tyneside...’

I can provide no definite information on who Mr Swaddle or Mr Winship were – though I am sure that this knowledge exists. Certainly in the late 1860s and 1870s there was a well-known oarsman called Thomas Winship, who Ian Whitehead says was from ‘a well-known Tyne rowing family’. Between 1869 and 1871 he was part of the ‘Tyne Champion Four’ with Jimmy Renforth, James Taylor and John Martin. Their most notable victory came in 1870 when defeated the St John, New Brunswick crew, champions of North America, on Lake Lachine in Quebec.

There is a lot of research still to be done (particularly by reference to local newspapers) on the contribution of Swaddle and Winship to rowing in Britain. In fact, Swaddle’s influence went further afield as many of their boats were sold abroad. The Australian Town and Country Journal of 17 September 1880 noted that ‘The cost of a Swaddle and Winship wager boat delivered in Sydney, would be about £30’ (as the boat cost £18, the cost of delivery from Newcastle to Sydney was, presumably, £12). This information comes from Trove, a splendid online resource provided by the National Library of Australia consisting of a vast collection of digitised newspapers, books and images. Trove shows that Australian papers had many references to Swaddle’s boats taking part in numerous races in Australia (and in England) between 1876 and 1889. It was not just singles that were imported, in 1882 Melbourne Rowing Club had an eight sent over. These were their ‘glory years’ when the name of ‘Swaddle and Winship’ was respected not only on the Tyne and on the Thames but also on the Parramatta and the Yarra and, no doubt, on many other famous (and not so famous) courses throughout the rowing world.

Another typical race over the Tyne Championship Course. On 3 April 1882, Ned Hanlan (in a Phelps and Peters boat) beat R.W. Boyd (in a Swaddle and Winship boat) for the titles of both World and English Sculling Champion – and for a £1,000 prize. To get an idea of what this was worth, Ian Whitehead says that in 1870 an unskilled man would earn £1 a week and a skilled man £1.50. Thus, £1,000 could mean ten years pay for twenty minutes work.

*Bonny - a term used by people from the Tyneside region of North East England meaning ‘beautiful’.

** Notable exceptions are Harry Clasper: Hero of the North (1990) and Rowing: A Way Of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside (2003) by David Clasper, The Sporting Tyne: A History of Professional Rowing (2002) and James Renforth Champion Sculler of the World (2004) by Ian Whitehead, The Tyne Oarsmen: Harry Clasper, Robert Chambers, James Renforth (1993) by Peter Dillon. Chris Dodd is currently producing a work on Tyne rowing.

Tim Koch writes:

A recent HTBS posting asked about Swaddle and Winship boat builders, a Newcastle-on-Tyne firm which built much admired racing boats in the 1870s and 1880s. I cannot produce anything like the full story of the firm, but I can provide some background to their work plus some (fairly random) aspects of their history.

Newcastle’s High Level Bridge on the River Tyne, the starting point for many famous professional sculling races.

To the casual observer of British rowing history, it would be easy to get the idea that very little has happened beyond Putney and Henley or Oxford and Cambridge and I am probably one of those who are guilty of promulgating this idea. I cannot correct this is in one posting but it is true that Newcastle-on-Tyne, an industrial city in the North East of England born of mining and ship building, has made a very large contribution to the sport of rowing and to the art (or science) of boat building. By the mid-nineteenth century, rowing on the River Tyne was a massive spectator sport among ordinary working people and a lot of money was changing hands through betting. Many improvements in boat design and in rowing technique came out of Newcastle, most famously from its three favourite sons, Robert Chambers, James Renforth and, in particular, Harry Clasper.

An early painting of Harry Clasper. Rather like the painting of another Newcastle sculler, Edward Hawkes, this picture appears to have had Clasper’s head added at a later date. The depiction of the boat cannot be taken as entirely accurate either.

Professional scullers were the first sporting heroes of the industrial working class (long before soccer players took this role). These oarsmen were not the ‘gentlemen amateurs’ of London and the south, they were tough working men who needed their boats to go fast so they could make the big money that gambling brings. Then as now, for many people with a less than privileged start in life, success in sport or show business was the only conceivable way to improve their lot. For this reason (and unlike many of the conservative amateur oarsmen) professionals produced or readily adopted new innovations such as outriggers, carvel hulls, sliding seats, swivel rowlocks, overlapping handles and keel fins and adapted their rowing styles to fit the new equipment. Further, it is mostly forgotten that for a long time England had two famous ‘Championship Courses’ for boat racing. One was the 4-mile, 374-yard Putney to Mortlake course on the Thames and the other was the 3-mile, 570-yard High Level Bridge to the Scotswood Suspension Bridge course on the Tyne.

This illustration records a race typical of the calibre of those that took place on the Tyne Championship Course. After one of the greatest and most innovative of all scullers, Ned Hanlan, had become champion of Canada in 1877 and of the United States in 1878, he travelled to Britain in 1879 to take on the best the country could offer. The venue for his race against the English champion, William Elliott, was not on the Thames but was on the Tyne, before a crowd of 10,000. The Englishman used a Swaddle and Winship and Hanlan took two of the company’s boats back to the United States. The top picture shows the start at the High Level Bridge and the lower picture shows the finish at the Scotswood Suspension Bridge.

It should be of no surprise therefore that Newcastle should produce a highly respected firm of boat builders such as Swaddle and Winship. Rowing historian Eric Halladay held that by 1880 the three most important boat builders were John Hawks Clasper (a Newcastle man based in Putney), Sims of Putney and Swaddle and Winship of Scotswood, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

From references in The Times it seems that the Cambridge Boat Race crew used Swaddle’s boats from 1876 to 1883 and Oxford from 1878 to 1882. The firm’s ‘big break’ came in the 1876 University Boat Race when they built the winning craft. The quote below is from The Australian Town and Country Journal of 27 May 1876 (they may have taken it verbatim from a British publication such as Bell’s Life):

Cambridge (use) the new boat built for them by Swaddle and Winship, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, it having developed better qualities than their Searle boat... she is considerably lighter than their Searle... A novelty about the new ship is a somewhat peculiar arrangement of the ‘riggers,’ which dispenses with a consolable amount of the supporting woodwork and, as far as it can go, diminishes her weight... This is the first eight oar ever built in the north – at any rate in modern times – for either University, and should Cambridge win in her this year the firm of Swaddle and Winship is certain to become in great request, just as Clasper made his reputation as a builder by the boat in which Goldie first showed Cambridge the way to victory after a decade of defeat.

At least two of the eights Swaddle and Winship produced for the Boat Race became particularly well known, the Cambridge boat of 1877 and the Oxford boat of 1879.

Rowing historian Chris Dodd says this about the start of the 1877 ‘Dead Heat’ race it in his 1983 book, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race:

...the race started at 8.27am.... There was brilliant sun and a chilling wind, and Oxford had won the toss and chosen Middlesex, and were on the water first. Cambridge had a last minute panic about their Swaddle and Winship (boat). It was a short heavily cambered craft, and..... was very fast in calm water but stuck her nose into the wind if there was one, needing a great deal of rudder. The wind was from the west-northwest, the worst possible for Cambridge, and so they fixed a false keel to the boat at the last moment...

I am currently making a video for HTBS about the 1877 race and recently went to the River and Rowing Museum at Henley to interview Chris. To my delight, he produced what is alleged to be the bows of the boat made by Swaddle and Winship for CUBC in 1877. Unfortunately, it has no provenance beyond what is painted on it. It is illuminated with the names of the Oxford crew on one side and the Cambridge crew on the other. Both sides say ‘Portion of Boat used by Cambridge Crew. Dead heat.’

Allegedly the bow of the Swaddle and Winship boat used by Cambridge in the 1877 Boat Race. The Light Blue crew is recorded on the stroke (port) side....

... and the Dark Blues are on the bow (starboard) side.

As to the Oxford boat of 1879, The Times of 12 March 1884 had a report on a ‘sportsman’s exhibition’ held in London which included a display of racing boats.

The Oxford boat shown has been used in the (Boat Race) since 1879 [actually 1879 to 1882, TK], and is considered to be the best boat the Oxford crew has ever used. This was built by Swaddle and Winship of Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the same firm lent other specimens of boat building which have been used successfully in great races.

The 1879 Boat Race at Hammersmith. Between 1878 and 1882 both crews used Swaddle and Winship boats.

Of course, by implying that approval by the gentlemen amateurs of Oxford and Cambridge was the ultimate accolade, I continue to marginalise rowing outside of the south of England. My only (rather inadequate) defence is that the history of professional and north of England rowing has been sparsely recorded compared to amateur rowing in southern England.** Even successful amateurs from places like Tyneside are little remembered, men like William Fawcus of Tynemouth Rowing Club who won amateur sculling’s ‘Triple Crown’ in 1871 with victories in the Diamonds, Wingfields and Metropolitan. In his biography of Jimmy Renforth, Ian Whitehead complains that ‘He is largely forgotten by the natives of Tyneside...’

I can provide no definite information on who Mr Swaddle or Mr Winship were – though I am sure that this knowledge exists. Certainly in the late 1860s and 1870s there was a well-known oarsman called Thomas Winship, who Ian Whitehead says was from ‘a well-known Tyne rowing family’. Between 1869 and 1871 he was part of the ‘Tyne Champion Four’ with Jimmy Renforth, James Taylor and John Martin. Their most notable victory came in 1870 when defeated the St John, New Brunswick crew, champions of North America, on Lake Lachine in Quebec.

There is a lot of research still to be done (particularly by reference to local newspapers) on the contribution of Swaddle and Winship to rowing in Britain. In fact, Swaddle’s influence went further afield as many of their boats were sold abroad. The Australian Town and Country Journal of 17 September 1880 noted that ‘The cost of a Swaddle and Winship wager boat delivered in Sydney, would be about £30’ (as the boat cost £18, the cost of delivery from Newcastle to Sydney was, presumably, £12). This information comes from Trove, a splendid online resource provided by the National Library of Australia consisting of a vast collection of digitised newspapers, books and images. Trove shows that Australian papers had many references to Swaddle’s boats taking part in numerous races in Australia (and in England) between 1876 and 1889. It was not just singles that were imported, in 1882 Melbourne Rowing Club had an eight sent over. These were their ‘glory years’ when the name of ‘Swaddle and Winship’ was respected not only on the Tyne and on the Thames but also on the Parramatta and the Yarra and, no doubt, on many other famous (and not so famous) courses throughout the rowing world.

Another typical race over the Tyne Championship Course. On 3 April 1882, Ned Hanlan (in a Phelps and Peters boat) beat R.W. Boyd (in a Swaddle and Winship boat) for the titles of both World and English Sculling Champion – and for a £1,000 prize. To get an idea of what this was worth, Ian Whitehead says that in 1870 an unskilled man would earn £1 a week and a skilled man £1.50. Thus, £1,000 could mean ten years pay for twenty minutes work.

*Bonny - a term used by people from the Tyneside region of North East England meaning ‘beautiful’.

** Notable exceptions are Harry Clasper: Hero of the North (1990) and Rowing: A Way Of Life - The Claspers of Tyneside (2003) by David Clasper, The Sporting Tyne: A History of Professional Rowing (2002) and James Renforth Champion Sculler of the World (2004) by Ian Whitehead, The Tyne Oarsmen: Harry Clasper, Robert Chambers, James Renforth (1993) by Peter Dillon. Chris Dodd is currently producing a work on Tyne rowing.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

What the Rower Reaps

What the Rower Reaps

I sow the field of the bay

with passage. I sow

the morning with the ineffable

motion of arms to oars.

I grow the crop of effort.

I harvest the satisfaction

of having intersected

with the elements.

Philip Kuepper

(1 December 2013)

I sow the field of the bay

with passage. I sow

the morning with the ineffable

motion of arms to oars.

I grow the crop of effort.

I harvest the satisfaction

of having intersected

with the elements.

Philip Kuepper

(1 December 2013)

Saturday, February 22, 2014

No Rowing History Forum in Mystic this Spring

Attendees at the 2012 Rowing History Forum in Mystic.

A very popular event for rowing historians and those interested in rowing history is the Rowing History Forum. This Forum is organised by the River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames, England, and the Friends of Rowing History (with the help of the museum Mystic Seaport) in Mystic Connecticut, USA. Last year, in October, the museum in Henley arranged a marvellous event, which was reported by HTBS’s Tim Koch. Read his report here.

As the River and Rowing Museum took care of it last year, it was time for the Americans to organise it this spring. However, I am sad to have to report that, unfortunately, there will not be a Rowing History Forum this spring at Mystic Seaport, which houses the rowing exhibit “Let Her Run” and the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

I am not even sure if there will be a Rowing History Forum organised in America later this year. If we hear anything differently, we will of course post the news immediately on HTBS.

A very popular event for rowing historians and those interested in rowing history is the Rowing History Forum. This Forum is organised by the River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames, England, and the Friends of Rowing History (with the help of the museum Mystic Seaport) in Mystic Connecticut, USA. Last year, in October, the museum in Henley arranged a marvellous event, which was reported by HTBS’s Tim Koch. Read his report here.

As the River and Rowing Museum took care of it last year, it was time for the Americans to organise it this spring. However, I am sad to have to report that, unfortunately, there will not be a Rowing History Forum this spring at Mystic Seaport, which houses the rowing exhibit “Let Her Run” and the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

I am not even sure if there will be a Rowing History Forum organised in America later this year. If we hear anything differently, we will of course post the news immediately on HTBS.

Friday, February 21, 2014

Play Up, Play Up & Play THE Game

Greg Denieffe writes:

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the British Army had approximately 710,000 men at its disposal. The years 1914 and 1915 were known as the years of the Volunteer Army, but in January 1916 conscription was introduced for single men aged 18-41. Recruitment posters played an important part both before and after its introduction.

Lord Kitchener (Secretary of State for War) believing that overwhelming manpower was the key to winning the War, set about looking for ways to encourage men of all classes to join up. General Sir Henry Rawlinson suggested that men would be more inclined to enlist in the Army if they knew that they were going to serve alongside their friends and work colleagues. He appealed to London stockbrokers to raise a battalion of men from workers in the City of London and by the end of August 1914, 1,600 men had enlisted in the 10th (Service) Bn. Royal Fusiliers, the first ‘Pals Battalion’ and the so-called ‘Stockbrokers’ Battalion’.

The 1st Sportsmen’s Battalion – The 23rd (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers was formed in September 1914 and was made up of men who had made their name in sports such as cricket, boxing and football. This battalion proved so popular that a 2nd Sportsmen’s Battalion – The 24th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers followed in November 1914. The recruitment poster (above) does not play (pun intended) on the sporting prowess of potential recruits. Perhaps this is why the BBC in the first episode of Britain’s Great War called War Comes to Britain used an Australian Imperial Force (AIF) recruitment poster when discussing the Pals Battalions (28:00-29:30).

In Australia, the outbreak of the War was greeted with enthusiasm. Even before Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, it had pledged its support alongside other states of the British Empire and almost immediately began preparations to send forces overseas to participate in the conflict. Like Britain, as the war went on, casualty rates increased and the number of volunteers declined but unlike in Britain, the issue of conscription was put to a public vote, firstly in October 1916 and again in December 1917. On both occasions the country voted ‘No’ to conscription.

The 1916 AIF enlistment poster featured in the BBC documentary Britain’s Great War.

In 1916 the AIF launched a poster campaign aimed at recruiting a battalion of sportsmen into the defence forces to be known as The Sportsmen’s 1000. The artwork featured a portrait of Lieutenant Albert Jacka with images on each side of the portrait of cricketers, men playing bowls, golf and tennis; sculling and yachting, horse and car racing, hockey, boxing and Australian rules football. Jacka was the first Australian to receive the Victoria Cross during the First World War for his bravery at Gallipoli. The VC appears on his chest with the words: “Sports” The medal of medals.

It was said that one of the reasons Jacka was such a good soldier, and had such a fighting attitude, was that he had been a boxer before the war. The campaign to enlist sportsmen was fuelled by a strong belief that by playing sport, young men developed specific skills and qualities that could be used on the battlefield.

Albert Jacka’s military career was one of outstanding bravery. He enlisted in September 1914 in the AIF and landed in Gallipoli on 26 April 1915. For his action on 19 May 1915 he was awarded the Victoria Cross, the first for the AIF in the First World War, instantly becoming a national hero. He quickly rose through the ranks and on 29 April 1916 was commissioned second lieutenant. He received a Military Cross for action at Pozieres in August 1916 and a bar for action at Bullencourt in April 1917. He received his commission as captain on 15 March 1917. Wounded twice and then gassed in May 1918, he saw no more action. He returned to Melbourne to a hero’s welcome in 1919. He was demobilised in 1920 and died at the age of 39 on 17 January 1932. At his funeral, Jacka was described as ‘Australia's greatest front-line soldier’.

You can see why he won his VC in this short video:

AIF enlistment poster produced in 1917.

This poster, published by the State Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, depicts Lieut. Jacka VC, as a role model for a huge campaign to enlist more sportsmen into the Australian Imperial Force in 1917. It features two common recruiting devices used in Australia, a well-known local soldier and a target number of men required for a specially named group. In the centre is an oarsman, carrying his oar like of a pikeman of old, surrounded by other sportsmen as they are summoned by Jacka to ‘Enlist in the Sportsmen’s Thousand’ and ‘Show the enemy what Australian sporting men can do’. It is interesting to see that the word ‘thousand’ has replaced the number ‘1000’ from the earlier poster.

In another AIF enlistment poster (below), probably from 1917, the number ‘1000’ is back on the poster; in the upper right hand corner are attributes of sportsmen, among them also an oar.

It may be stretching poetic licence to suggest that the following poem by Australian C. J. Dennis is using the word ‘rowing’ as we on HTBS are wont to do, but it sums up the spirit that the recruitment posters tried to convey.

From The Moods of Ginger Mick – IV. “The Push” (1916):

But they took ‘im an’ they drilled ‘im an’ they shipped ‘im overseas

Wiv a crowd uv blokes ‘e never met before.

‘E rowed wiv ‘em, an’ scrapped wiv ‘em, an’ done some tall C.B.’s,

An’ ‘e lobbed wiv ‘em on Egyp’s sandy shore.

Then Pride o’ Race lay ‘olt on ‘im, an’ Mick shoves out ‘is chest

To find ‘imself Australian an’ blood brothers wiv the rest.

Back in Blighty, the Sportsmen’s Battalions continued to advertise for recruits but their enlistment posters continued to be dull and uninspiring.

This could not be said about the battalions formed primarily with the aim of recruiting professional footballers in both Scotland and England. In Scotland in November 1914, the full football team from Heart of Midlothian, players from Hibernian, Raith Rovers and Dunfermline, together with golfers, rugby players and their fans joined what became known as MacRae's Battalion, officially the 16th Royal Scots. They were also known as ‘The Sporting Battalion’.

December 1914 saw the formation of The Football Battalion (The 17th Service Battalion, Middlesex Regiment). There is a fine example of their recruitment poster in a previous HTBS post called 'Lions not Donkeys'. Players from Clapton Orient (now Leyton Orient) were the first English Football League club to enlist together. Following the example of club captain, Fred Parker, around 40 players and staff volunteered and it soon went on to attract players from other clubs.

Recruitment poster for The Football Battalion, similar to the one above with the words ‘on the Field of Honour’ replaced with ‘and Join the Football Battalion’.

‘This is not the time to play games’ was the theme of a speech by Lord Roberts seeking to persuade sportsmen to enlist. This poster depicts a Rugby Union player with a cheering crowd behind him, mirrored by a soldier holding a rifle instead of a rugby ball.

1919 ‘Sportsmen and Smart Men’ wanted for the RMF.

When the First World War finally ended in 1918, the world had changed forever. What hadn’t changed was the use of images of sportsmen to entice young men to ‘join up’. This is a nice example of a recruitment poster from 1919 for the Royal Munster Fusiliers, one of eight Irish infantry regiments in the British Army. It uses images of soccer and hockey, boxers and athletes, a tug-of-war team and a cricketer; hardly traditional Irish sports – there was no room for sports like hurling, Gaelic football or handball. The tag line A Good Clean Sporting Life is offered with an Assured Future was also to prove short-sighted as in 1922 five of the eight were disbanded on the establishment of the Irish Free State. It wasn’t only the world at large that was changing.

Thursday, February 20, 2014

The Coxswain

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Silver Trophies from 1866 to 2014

|

| The Mulholland Cup (1866) |

I really enjoyed the recent coverage that HTBS has been privileged to give the new silver trophy for the Newton Women's Boat Race. In 2011, HTBS posted my history of The Mulholland Cup (1866) and also mentioned a project by the Naughton Gallery at Queen’s University, Belfast, called Silver Sounds.

Silver Sounds was a project that suggested that sound might be a way of uniting and reinterpreting Queen’s University’s silver collection. The soundscapes created for the project respond to the provenance of a particular piece of silverware and explore the reasons for its creation, donation and use and combine with the silver objects to create a new immersive artwork.

Jason Geistweidt is a sound artist currently based in Chicago. He was one of the twelve artists commissioned to create a piece for the project and he based it on The Mulholland Cup. His piece responds to the continual transformation of the sporting trophy as dates and names were added every few years as well as its static embodiment of particular events and memories etched in metal. Wishing to create a kinetic complement, he has incorporated elements which provide this object with a living context: the working of metal, the pull of the oar through water and the encouragement of the coxswain.

|

| Newton Women's Boat Race (2014) |

Unfortunately, the sound piece created by Jason was not available when HTBS originally posted the article back in 2011 but I have recently discovered a copy and have uploaded it to the online audio distribution platform SoundCloud. You can listen to the six minute recording here.

I would like to think that Rod Kelly, the silversmith responsible for the new Newton trophy, would appreciate what Geistweidt created as much as we at HTBS appreciate what he has produced for the sport of rowing in 2014.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

The Glittering Prize

Esther Momcilovic (President, CUWBC) and Maxie Scheske (President, OUWBC) with the trophy that each hope to hold aloft on 30 March.

Tim Koch writes:

As a postscript to yesterday’s post on the new trophy commissioned by sponsor Newton Investment Management for the Oxford-Cambridge Women’s Boat Race, I can report that yesterday morning it was officially unveiled and presented to both Boat Clubs and to the Boat Race Company.

A press release informs us:

The trophy is four sided and handmade in silver, each side the shape of a blade’s spoon with chased embossed patterns of flowing water. Imposed on each spoon is the bow of a boat cutting through the water. The main body is supported by four ebony columns representing the looms of four blades. Several of the chased details on the trophy are inlaid with pure gold. The base has four sides. Two of the sides represent the Clubs with symbolism chosen by themselves, a lion for Cambridge and a crown for Oxford; while the other two sides are chased with apples balanced on a scale, these are representative of the sponsor’s involvement and their belief in balance, equality and diversity in sport. On the underside there is a silver plate with records of all previous winners dating back to 1927, and from this year the new winners will be engraved visibly on the top of the trophy. The trophy weighs 5.5kgs and measures 50cms high.

From left to right: Rod Kelly, the designer of the trophy and one of the UK’s leading silversmiths, Helena Morissey, CEO of Newton Investment Management and campaigner for gender equality in business, Richard Gillespie, Chairman of The Boat Race Company Ltd, and Chris Dodd, writer on rowing and historian at the River and Rowing Museum. Chris is accepting the former prize for the Women’s Boat Race, a wooden shield, on behalf of the museum. Helena Morissey said that the shield looked like it was purchased at a heel bar and I though it resembled something awarded to a pub darts team.

Designer Rod Kelly shows the underside of the trophy where the winners of all the races held between 1927 and 2013 are recorded.

While Newton must be thanked for making this fine piece of work possible, their real contribution since 2011 has been to invest in coaching and equipment for OUWBC and CUWBC, ultimately to prepare them for 2015 and beyond when they will race on the Tideway on ‘Boat Race Day’ proper. The real importance of the new trophy is that it compares equally with the prize for the men’s race. The picture below was taken in 2013 and shows the shield then awarded to the winner of the women's race next to the impressive trophy given to the men. The unavoidable implication was that the women’s contest was the poor relation of the two. The new trophy, however, sends out a very different message.

March 2013: article writer Tim puts on his ‘unimpressed face’ when comparing the two prizes.

Tim Koch writes:

As a postscript to yesterday’s post on the new trophy commissioned by sponsor Newton Investment Management for the Oxford-Cambridge Women’s Boat Race, I can report that yesterday morning it was officially unveiled and presented to both Boat Clubs and to the Boat Race Company.

A press release informs us:

The trophy is four sided and handmade in silver, each side the shape of a blade’s spoon with chased embossed patterns of flowing water. Imposed on each spoon is the bow of a boat cutting through the water. The main body is supported by four ebony columns representing the looms of four blades. Several of the chased details on the trophy are inlaid with pure gold. The base has four sides. Two of the sides represent the Clubs with symbolism chosen by themselves, a lion for Cambridge and a crown for Oxford; while the other two sides are chased with apples balanced on a scale, these are representative of the sponsor’s involvement and their belief in balance, equality and diversity in sport. On the underside there is a silver plate with records of all previous winners dating back to 1927, and from this year the new winners will be engraved visibly on the top of the trophy. The trophy weighs 5.5kgs and measures 50cms high.

From left to right: Rod Kelly, the designer of the trophy and one of the UK’s leading silversmiths, Helena Morissey, CEO of Newton Investment Management and campaigner for gender equality in business, Richard Gillespie, Chairman of The Boat Race Company Ltd, and Chris Dodd, writer on rowing and historian at the River and Rowing Museum. Chris is accepting the former prize for the Women’s Boat Race, a wooden shield, on behalf of the museum. Helena Morissey said that the shield looked like it was purchased at a heel bar and I though it resembled something awarded to a pub darts team.

Designer Rod Kelly shows the underside of the trophy where the winners of all the races held between 1927 and 2013 are recorded.

While Newton must be thanked for making this fine piece of work possible, their real contribution since 2011 has been to invest in coaching and equipment for OUWBC and CUWBC, ultimately to prepare them for 2015 and beyond when they will race on the Tideway on ‘Boat Race Day’ proper. The real importance of the new trophy is that it compares equally with the prize for the men’s race. The picture below was taken in 2013 and shows the shield then awarded to the winner of the women's race next to the impressive trophy given to the men. The unavoidable implication was that the women’s contest was the poor relation of the two. The new trophy, however, sends out a very different message.

March 2013: article writer Tim puts on his ‘unimpressed face’ when comparing the two prizes.

Monday, February 17, 2014

A Trophy Worthy of the Chase

Silversmith Rod Kelly has put in 520 hours of punch-and-hammer to create the new trophy for the Newton Oxford and Cambridge Women’s Boat Race.

Today, the new trophy for the Newton Women's Boat Race will be officially unveiled. Rowing historian and writer Christopher Dodd, who has interviewed Rod Kelly, the silversmith who made the trophy, writes exclusively for HTBS:

Newton, sponsor of the women’s Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, has commissioned a trophy to mark the event’s move from the Thames at Henley to the men’s course at Putney in 2015. The trophy will be awarded to the winners of this year’s race on 30 March (at Henley, but floods suggest it may move to Dorney or Holme Pierrepont). The pot will have winners since 1927 engraved on its plinth and will make the symbolic journey from the non-tidal 2,000 metres to four and a quarter miles on the Tideway.

Two things stand out about the new trophy. First, this is no requisitioned silverware from a long lost event, nor an off-the-shelf pot with the Newton Boat Race engraved on it. This is a serious and imaginative piece of kit. Newton commissioned it from the silversmith Rod Kelly, and it was crafted to his design in his Shetland studio.

The second standout is that Newton has safeguarded a long life for the trophy by ruling out the inclusion of the company’s name. ‘This is about the girls who race, not about Newton’, Claire Blackwell, the head of marketing at the investment house, says. ‘Our raison d’être is equality, diversity and balance.’ Kelly describes this as a brave decision. It is such a relief not to be briefed that a client’s name must be in a certain size in the front, he says.

The men’s race has had three trophies so far, the first from Ladbroke, the second from Beefeater and the third from Aberdeen Asset Management, the latter being the handsome quaich (or Scottish drinking vessel) used by the current sponsors BNY Mellon. Whoever sponsors the women’s race after Newton will not be embarrassed by a piece with somebody else’s name on it.

Kelly, who has an impressive list of past clients and whose work appears in prestigeous museums, was born in Reading and remembers Boat Race Day as a big occasion for his family. He studied in Birmingham and at the Royal College of Art and now divides his time between Norfolk and Shetland.

His first meeting with Newton was on 13 August 2013. In October he spent a day with Cambridge’s women at Ely and took 200 pictures of patterns water, hulls, oars, movement and light on Ouse water. He came away intrigued by the mental approach to rowing as well as the physical attributes. Kelly likes to make pieces that tell a story, and he left Ely with a story. A story of application to the job in hand, the sculpting of water, blades, boats to represent the race and apples to represent balance and equity espoused by the sponsor.

After a meeting with Newton and both clubs to finalise the design, Kelly went off to Shetland (catching the Aberdeen universities boat race in transit) to begin the design process. He built a cardboard model of his concept that he amended gradually as it sat in his kitchen. He decided on a square shape and began to feel it – ‘You have to really feel it, that it will be recognised as the Newton Trophy’.

‘A square form catches the light and is very photogenic’, he says. There are waves and an oar blade depicted on each side, a lip on which to engrave future results, and the vase is mounted on four ebony pillars to represent oars. Two sides of the base have a ‘Newton’ image of two apples on a balance. The Oxford side has a crown and the Cambridge side a lion, both with pure gold inlaid details. Past results will be on a plinth below.

The model in the kitchen spoke and announced to Kelly that it should be increased in size by 25 per cent to stand 50 cm tall. This meant starting again, because enlargement requires adjusting the proportion of the parts rather than lumping a percentage on.

Once satisfied with the model, Kelly ordered the sheets of silver – 1.1 mm thick, and cutting by hand and chasing (embossing using small punches and hammer) began. Work progressed at an hour a square inch – for example, Cambridge’s lion took two days. There are about 100 soldered joints, and the ebony pillars were fashioned from blanks for snooker cues.

The Newton trophy was finished on 1 February and taken to the Goldsmiths’ Company for hallmarking. Kelly has put in 520 hours of punch-and-hammer to create it, and very fine it is too. To put that in context, that represents about 1560 pulls from Putney to Mortlake in an eight.

The hope is that the women’s race becomes a contest worthy of its trophy from 2015 – that it doesn’t take a century and more to make a really good race of it, as the men’s did.

Today, the new trophy for the Newton Women's Boat Race will be officially unveiled. Rowing historian and writer Christopher Dodd, who has interviewed Rod Kelly, the silversmith who made the trophy, writes exclusively for HTBS:

Newton, sponsor of the women’s Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, has commissioned a trophy to mark the event’s move from the Thames at Henley to the men’s course at Putney in 2015. The trophy will be awarded to the winners of this year’s race on 30 March (at Henley, but floods suggest it may move to Dorney or Holme Pierrepont). The pot will have winners since 1927 engraved on its plinth and will make the symbolic journey from the non-tidal 2,000 metres to four and a quarter miles on the Tideway.

Two things stand out about the new trophy. First, this is no requisitioned silverware from a long lost event, nor an off-the-shelf pot with the Newton Boat Race engraved on it. This is a serious and imaginative piece of kit. Newton commissioned it from the silversmith Rod Kelly, and it was crafted to his design in his Shetland studio.

The second standout is that Newton has safeguarded a long life for the trophy by ruling out the inclusion of the company’s name. ‘This is about the girls who race, not about Newton’, Claire Blackwell, the head of marketing at the investment house, says. ‘Our raison d’être is equality, diversity and balance.’ Kelly describes this as a brave decision. It is such a relief not to be briefed that a client’s name must be in a certain size in the front, he says.

The men’s race has had three trophies so far, the first from Ladbroke, the second from Beefeater and the third from Aberdeen Asset Management, the latter being the handsome quaich (or Scottish drinking vessel) used by the current sponsors BNY Mellon. Whoever sponsors the women’s race after Newton will not be embarrassed by a piece with somebody else’s name on it.

Kelly, who has an impressive list of past clients and whose work appears in prestigeous museums, was born in Reading and remembers Boat Race Day as a big occasion for his family. He studied in Birmingham and at the Royal College of Art and now divides his time between Norfolk and Shetland.

His first meeting with Newton was on 13 August 2013. In October he spent a day with Cambridge’s women at Ely and took 200 pictures of patterns water, hulls, oars, movement and light on Ouse water. He came away intrigued by the mental approach to rowing as well as the physical attributes. Kelly likes to make pieces that tell a story, and he left Ely with a story. A story of application to the job in hand, the sculpting of water, blades, boats to represent the race and apples to represent balance and equity espoused by the sponsor.

After a meeting with Newton and both clubs to finalise the design, Kelly went off to Shetland (catching the Aberdeen universities boat race in transit) to begin the design process. He built a cardboard model of his concept that he amended gradually as it sat in his kitchen. He decided on a square shape and began to feel it – ‘You have to really feel it, that it will be recognised as the Newton Trophy’.

‘A square form catches the light and is very photogenic’, he says. There are waves and an oar blade depicted on each side, a lip on which to engrave future results, and the vase is mounted on four ebony pillars to represent oars. Two sides of the base have a ‘Newton’ image of two apples on a balance. The Oxford side has a crown and the Cambridge side a lion, both with pure gold inlaid details. Past results will be on a plinth below.

The model in the kitchen spoke and announced to Kelly that it should be increased in size by 25 per cent to stand 50 cm tall. This meant starting again, because enlargement requires adjusting the proportion of the parts rather than lumping a percentage on.

Once satisfied with the model, Kelly ordered the sheets of silver – 1.1 mm thick, and cutting by hand and chasing (embossing using small punches and hammer) began. Work progressed at an hour a square inch – for example, Cambridge’s lion took two days. There are about 100 soldered joints, and the ebony pillars were fashioned from blanks for snooker cues.

The Newton trophy was finished on 1 February and taken to the Goldsmiths’ Company for hallmarking. Kelly has put in 520 hours of punch-and-hammer to create it, and very fine it is too. To put that in context, that represents about 1560 pulls from Putney to Mortlake in an eight.

The hope is that the women’s race becomes a contest worthy of its trophy from 2015 – that it doesn’t take a century and more to make a really good race of it, as the men’s did.

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Showing some Legs... 2

‘L’Enfant Terrible at Henley: “Oh! nurse, look at his little trousers”’. The Sketch, 12 July 1893.

A contribution from Tim Koch.

Saturday, February 15, 2014

Long To Rain Over Us?

Flood warnings in force in the UK on 14 February. ©The Environment Agency.

Tim Koch writes:

Readers in Britain will not need to be told that large parts of England and Wales are in ‘flood crisis’. Since before Christmas, rising sea, river surface and ground water plus abnormally strong winter storms have caused severe flooding in low lying (and some not so low lying) areas. Correctly or not, there has been strong criticism of the Environment Agency, the body that is responsible for the management of rivers in England, and of the Government. While rural parts of the country, notably parts of the county of Somerset, have been affected for months, there is a view that the authorities have only started to take decisive action since affluent areas near London have been flooded. The crisis is far from over and the worse may still be to come. It is probably a little insensitive to talk about how rowing has been affected when a lot of people have suffered great misery so I will let the following pictures, culled from various rowing club web sites and twitter accounts, tell their own story.

Sign of the times. The rowing course at the National Water Sports Centre in Nottingham on 3 February. It seems to have grown from six to twelve lane. Picture: @nwscnotts.

‘Leander Island’ on 8 January. The river should only be on one side of the pontoon (dock) in front of the Pink Palace. Picture: © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Looking down the Henley course. The river should be to the left of the trees in the middle of the watercourse. The land used for the Henley Stewards’ Enclosure, boat tent area and trailer park is all under water. © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Looking towards Temple Island and the HRR start. © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Pumping out floodwater, Henley Rowing Club, 9 January. Picture: @CoachBethan.

The River and Rowing Museum car park in November. Picture: www.henleywhalers.org.uk

The Henley Standard newspaper has put this aerial video online: http://www.henleystandard.co.uk/news/news.php?id=39393#vid

The boathouse at the Redgrave Pinsent Rowing Lake near Reading, Berkshire, 10 February. Picture: Pete Reed.

Weybridge Rowing Club, Surrey, 9 February. Picture: www.weybridgerowing.co.uk

Worcester Rowing Club, 5 January. WRC often floods in a ‘normal’ year and crews rowing over the neighbouring horse racing course seems to be an almost annual event. Picture: @worcesterrowing.

Monmouth Rowing Club, Wales, 11 February. Perhaps not everyone is unhappy with the flooding. Picture: @RossGazette.

Tim Koch writes:

Readers in Britain will not need to be told that large parts of England and Wales are in ‘flood crisis’. Since before Christmas, rising sea, river surface and ground water plus abnormally strong winter storms have caused severe flooding in low lying (and some not so low lying) areas. Correctly or not, there has been strong criticism of the Environment Agency, the body that is responsible for the management of rivers in England, and of the Government. While rural parts of the country, notably parts of the county of Somerset, have been affected for months, there is a view that the authorities have only started to take decisive action since affluent areas near London have been flooded. The crisis is far from over and the worse may still be to come. It is probably a little insensitive to talk about how rowing has been affected when a lot of people have suffered great misery so I will let the following pictures, culled from various rowing club web sites and twitter accounts, tell their own story.

Sign of the times. The rowing course at the National Water Sports Centre in Nottingham on 3 February. It seems to have grown from six to twelve lane. Picture: @nwscnotts.

‘Leander Island’ on 8 January. The river should only be on one side of the pontoon (dock) in front of the Pink Palace. Picture: © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Looking down the Henley course. The river should be to the left of the trees in the middle of the watercourse. The land used for the Henley Stewards’ Enclosure, boat tent area and trailer park is all under water. © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Looking towards Temple Island and the HRR start. © Robert Treharne Jones/Leander Club.

Pumping out floodwater, Henley Rowing Club, 9 January. Picture: @CoachBethan.

The River and Rowing Museum car park in November. Picture: www.henleywhalers.org.uk

The Henley Standard newspaper has put this aerial video online: http://www.henleystandard.co.uk/news/news.php?id=39393#vid

The boathouse at the Redgrave Pinsent Rowing Lake near Reading, Berkshire, 10 February. Picture: Pete Reed.

Weybridge Rowing Club, Surrey, 9 February. Picture: www.weybridgerowing.co.uk

Worcester Rowing Club, 5 January. WRC often floods in a ‘normal’ year and crews rowing over the neighbouring horse racing course seems to be an almost annual event. Picture: @worcesterrowing.

Monmouth Rowing Club, Wales, 11 February. Perhaps not everyone is unhappy with the flooding. Picture: @RossGazette.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

)