Saturday, August 31, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Seven

You will find FISA’s race reports for the seventh day of the 2013 World

Rowing Championships on the Tangeum Lake regatta course in Chungju,

South Korea, here.

Friday, August 30, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Six

Thursday, August 29, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Five

You will find FISA’s race reports for the fifth day of the 2013 World

Rowing Championships on the Tangeum Lake regatta course in Chungju,

South Korea, here.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Four

You will find FISA’s race reports for the fourth day of the 2013 World Rowing Championships on the Tangeum Lake regatta course in Chungju, South Korea, here.

With weather forecasts predicted storms to arrive in Chungju tomorrow, Thursday, the finals in the five Para-rowing events had to re-schedulled for today. Temperatures reaching 30+ Celsius and under cloudy skies and almost flat water, it was ideal conditions for racing. FISA’s race reports are here.

With weather forecasts predicted storms to arrive in Chungju tomorrow, Thursday, the finals in the five Para-rowing events had to re-schedulled for today. Temperatures reaching 30+ Celsius and under cloudy skies and almost flat water, it was ideal conditions for racing. FISA’s race reports are here.

1936 Olympic Trial Video - Washington Winning by a Boat Length

Daniel James Brown's great book The Boys in the Boat is still on many rowers mind, and non-rowers, too, if I understand it right, this week being on the 17th place on the New York Times non-fiction best-seller list. HTBS wrote a book review about the it on 19 August. That post has got some interesting comments, and yesterday 'bob' sent along a link to a newsreel showing how Washington beat Penn by a boat length at the Olympic Trials at Princeton. Watch it here. Rumours have it that it was a photo finish race, but alas, it was not.... Now we know for certain, thanks to 'bob'!

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Three

You will find FISA’s race reports for the third day of the 2013 World Rowing Championships on the Tangeum Lake regatta course in Chungju, South Korea, here. As a storm with torrential rain is expected in the afternoon on Thursday, 29 August, races will be rescheduled with some heats being raced on Wednesday, 28 August. Read more about the changes here.

Monday, August 26, 2013

2013 World Rowing Championships - Day Two

You will find FISA’s race reports for the second day of the 2013 World Rowing Championships on the Tangeum Lake regatta course in Chungju, South Korea, here.

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Not just any old fat bloke...

Sir Steven Redgrave, the world most famous oarsman has been out paddling - it did not go that well.... Read about it here.

The 2013 World Rowing Championships have started

The 2013 World Rowing Championships have now started in Chungju, South Korea. Today’s racing included heats in ten boat classes on the Tangeum Lake International Rowing Regatta course. Read FISA's race reports here.

Friday, August 23, 2013

Rowing Standing Still

Rowing Standing Still

He stood there

going through the motions

in his mind,

slipping like silk

into the shell,

taking hold of the oars,

positioning them for rowing.

The water was another matter.

To imagine water was harder.

His mind could not get a grip

on the water, on the uncooperative

river. There was too much motion.

The river moved

every which way at once.

To overcome this he let

himself, shell, oars

simply flow

with the river in his mind,

the river of his imagination.

He let the embodied become liquid.

Once all had become

indistinct in his mind,

once he, shell, oars

had dissolved as one

with the river, he could begin

to row,

to row.

Philip Kuepper

(6 July, 2013)

He stood there

going through the motions

in his mind,

slipping like silk

into the shell,

taking hold of the oars,

positioning them for rowing.

The water was another matter.

To imagine water was harder.

His mind could not get a grip

on the water, on the uncooperative

river. There was too much motion.

The river moved

every which way at once.

To overcome this he let

himself, shell, oars

simply flow

with the river in his mind,

the river of his imagination.

He let the embodied become liquid.

Once all had become

indistinct in his mind,

once he, shell, oars

had dissolved as one

with the river, he could begin

to row,

to row.

Philip Kuepper

(6 July, 2013)

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

A Royal Tea Cruise

Gloriana flies the Royal Standard on the bow indicating that the Queen is on board. Photo © Sue Milton.

The tireless Malcolm Knight, a great promoter of traditional rowing, reports on a special event that took place on the River Thames on a hot day last July. HTBS has previously written about Malcolm in our report on the Tudor Pull.

Malcolm writes,

After six months, the plans were finally in place for the most important event so far in the life of the Queen’s Row Barge Gloriana.

The Royal Watermen who rowed wearing their heavy woolen costumes on one of the hottest days of the year.

On 9 July, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the company of the Duke and Duchess of Wessex, the Duke of York, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester and the Duke of Kent boarded QRB Gloriana at Albert Bridge, Home Park, Windsor, to be rowed by eighteen of the Royal Watermen under the helm of HM Barge Master Paul Ludwig for an afternoon tea cruise to celebrate the 60 years since her Coronation.

The Queen’s Barge Master, Paul Ludwig, and Malcolm Knight.

The Countess of Wessex chats to the Watermen. Sir Steve Redgrave, on the right, looks on.

The flotilla of four invited craft, under the control of Malcolm Knight aboard the Gentleman’s launch Verity, moved off upstream to the surprise and delight of other boats on the river. The QRB went up the weir stream to Eton College where invited members of staff and their families cheered the spectacle.

Malcolm Knight meets The Queen. On the right is Lord Sterling, the man who initiated the Gloriana project as a tribute to the Queen on Her Diamond Jubilee. He also provided much of the finance.

Whilst the Watermen took a well-earned breather, tea was provided to the Royal guests by the Waterside Inn after which the QRB turned and returned downstream to moor below Victoria Bridge where the Royal party went ashore.

The Queen and the Royal Party on the deck of the Gloriana. On the left is the Duke of Kent, a cousin of the Queen. Next to him is Brigitte, the Danish-born Duchess of Gloucester. To her left is Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, the Queen’s forth child. In the centre, Queen Elizabeth and a Waterman acting as coxswain. On the right of the group is Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, also a cousin of the Queen. Behind Richard, but obscured by a flag, is Prince Andrew, Duke of York, the Queen’s third child. His other rowing engagement this year in Vancouver, Canada, was also covered by HTBS. On the far right is Sophie, Countess of Wessex, the wife of Prince Edward.

The Queen thanks her Watermen at the end of her day on the river. The Earl of Wessex and the Duke of York followed on behind.

A ‘little piece of history’ was made as it is believed that this was the first time in nearly 200 years that a reigning monarch had been rowed in an 18-oared Royal barge by the Royal Watermen – a memorable day for all of us involved and one that has confirmed Gloriana as The Queen’s Row Barge.

The tireless Malcolm Knight, a great promoter of traditional rowing, reports on a special event that took place on the River Thames on a hot day last July. HTBS has previously written about Malcolm in our report on the Tudor Pull.

Malcolm writes,

After six months, the plans were finally in place for the most important event so far in the life of the Queen’s Row Barge Gloriana.

The Royal Watermen who rowed wearing their heavy woolen costumes on one of the hottest days of the year.

On 9 July, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the company of the Duke and Duchess of Wessex, the Duke of York, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester and the Duke of Kent boarded QRB Gloriana at Albert Bridge, Home Park, Windsor, to be rowed by eighteen of the Royal Watermen under the helm of HM Barge Master Paul Ludwig for an afternoon tea cruise to celebrate the 60 years since her Coronation.

The Queen’s Barge Master, Paul Ludwig, and Malcolm Knight.

The Countess of Wessex chats to the Watermen. Sir Steve Redgrave, on the right, looks on.

The flotilla of four invited craft, under the control of Malcolm Knight aboard the Gentleman’s launch Verity, moved off upstream to the surprise and delight of other boats on the river. The QRB went up the weir stream to Eton College where invited members of staff and their families cheered the spectacle.

Malcolm Knight meets The Queen. On the right is Lord Sterling, the man who initiated the Gloriana project as a tribute to the Queen on Her Diamond Jubilee. He also provided much of the finance.

Whilst the Watermen took a well-earned breather, tea was provided to the Royal guests by the Waterside Inn after which the QRB turned and returned downstream to moor below Victoria Bridge where the Royal party went ashore.

The Queen and the Royal Party on the deck of the Gloriana. On the left is the Duke of Kent, a cousin of the Queen. Next to him is Brigitte, the Danish-born Duchess of Gloucester. To her left is Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, the Queen’s forth child. In the centre, Queen Elizabeth and a Waterman acting as coxswain. On the right of the group is Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, also a cousin of the Queen. Behind Richard, but obscured by a flag, is Prince Andrew, Duke of York, the Queen’s third child. His other rowing engagement this year in Vancouver, Canada, was also covered by HTBS. On the far right is Sophie, Countess of Wessex, the wife of Prince Edward.

The Queen thanks her Watermen at the end of her day on the river. The Earl of Wessex and the Duke of York followed on behind.

A ‘little piece of history’ was made as it is believed that this was the first time in nearly 200 years that a reigning monarch had been rowed in an 18-oared Royal barge by the Royal Watermen – a memorable day for all of us involved and one that has confirmed Gloriana as The Queen’s Row Barge.

Monday, August 19, 2013

Book Review: The Boys in the Boat

The heroes in the boat: (from left) Stroke Donald ‘Don’ Hume (1915-2001), 7 Joseph ‘Joe’ Rantz (1914-2007), 6 George ‘Shorty’ Hunt (1916-1999), 5 Jim ‘Stub’ McMillin (1914-2005), 4 John ‘Johnny’ White (1916-1997), 3 Gordon ‘Gordy’ Adam (1915-1992), 2 Charles ‘Chuck’ Day (1914-1962), Bow Roger Morris (1915-2009) and, kneeling, Cox Robert ‘Bobby’ Moch (1914-2005).

Although rowing – or as it is called in America, crew – is a minor sport compared to other team games, each and every year sees a new book published about this aquatic activity. Nevertheless, it is rare to be able to add a new title to the niche genre of rowing history. Amongst the authors and the books which are still in print in this group, and worth mentioning here, you will find: David Halberstam’s The Amateurs (hardcover 1986; paperback 1996), Daniel Boyne’s two books The Red Rose Crew (2000; 2005) and Kelly: A Father, A Son, An American Quest (2008, 2012), and Christopher Dodd’s Pieces of Eight (published in Great Britain, 2012).

To this small, but splendid collection of authors and their books can now be included Daniel James Brown and his The Boys in the Boat – Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (Viking, 2013, 404 pp.). As the subtitle tells, Brown’s book is about the U.S. eight with coxswain who went to fight for honour and glory at the 1936 Olympic rowing regatta on lake Langer See at Grünau, outside Berlin, where these young American oarsmen became Olympic champions by a slim margin.

All Americans love a tale about underdogs, especially if the underdogs are Americans, and at the center of this compelling story is Joe Rantz, one of the boys in the crew, whom Brown met at his neighbour Judy Willman’s house; Judy was Joe’s daughter, and when Joe was diagnosed with cancer, he lived with her his remaining days. Listening to the old oarsman’s account, Brown realized that the story of these Olympians is not as commonly known as, for example, Jesse Owens’s, whose four golds at the Berlin Games gave the Nazis’ ideology of the Aryan race superiority a severe dent.

The sons of farmers, fishermen and lumberjacks forming the Husky crews are getting a little different ‘workout’ sawing through a big log of Douglas spruce. Photograph from 1929. Courtesy of Thomas E Weil.

While rowing back in the 1930s was regarded as a sport for the privileged few, Joe and his oarsmen comrades at the University of Washington were the sons of farmers, fishermen, and lumberjacks. Although Brown’s narrative is about all the boys in the boat – their way from freshmen on Lake Washington to Olympians on Langer See, a three- to four-year voyage not always on an easy, straight course – it is the human story of young Joe’s struggling life of Dickensian dimensions during the Depression that grabs hold of the reader.

Assisting the Husky crews was a remarkable group of rowing men: University of Washington’s head coach Al Ulbrickson, known as “the Dour Dane,” freshman coach Tom Bolles, who later became a successful coach for Harvard crews (both on the right); and boat builder George Pocock, the Englishman whose father had built boats for the “wet-bobs” at Eton College. George Pocock also helped to coach the Husky boys, using the same techniques he used to build the best racing shells in America: a philosophical approach and a sharp eye. It is as Brown writes, “Great crews are carefully balanced blends of both physical abilities and personality types.”

However, when Ulbrickson had found the perfect combination of nine men, they still had to beat the arch-rival crew from California-Berkeley, coached by Ky Ebright, whose previous crews had represented the U.S. in both the 1928 and 1932 Olympic Games. Then Joe and his mates had to overpower the “snobs” from the East Coast at the 1936 IRA Regatta at Poughkeepsie – this was a time when an incredible number of 90,000 spectators gathered on the shores of the Hudson to watch the races. In the Pocock-built Husky Clipper, the Huskies prevailed (told by the author in a beautiful race report). *Later winning the Olympic Trials in Princeton, it seemed the Washington crew had their trip to Berlin in the bag, but not before good people in Seattle and in the boys’ hometowns managed to raise $5,000 in a few days for their tickets.

In their first heat at Grünau, the Americans managed to keep the British eight at bay, forcing them to a repechage heat, an extra race which they won, taking them to the final, where strong crews from Germany and Italy were all game for the Olympic medals. It was the British boat, stroked by the eminent “Ran” Laurie and coxed by Noel Duckworth – two of my rowing heroes – that the Huskies feared most. In the final race, in front of Der Führer and other Nazi dignitaries, the Husky Clipper sneaked up from the far back of the field to snatch the gold medal, leaving the silver medal to the Italians and the bronze medal to the Germans, and the Brits with nothing, coming in fourth.

Daniel James Brown is a clever author and it is a grand story he is telling. He is not a rower himself, which is probably good, because he has made sure that a non-rower can easily follow the Husky boys when they catch a crab or feel the pain like they do after a hard race on Lake Washington. On the other hand there are also some oddities in his narrative. About Ran Laurie, Brown writes:

In the British boat, Ran Laurie dug furiously at the water. He was still relatively fresh. He wanted to do more. But like many British strokes in those days, he was wielding an oar with a smaller, narrower blade than the rest of his crew – the idea being that the stroke’s job was to set the pace, not to power the boat. With the small blade, he avoided the risk of burning himself out and losing his form.

No, I do not think that Laurie, one of the great Cambridge strokes before the Second World War, had a more narrow blade than the rest of his crew – honestly, it would not be cricket! Oarsmen might have individually adjusted riggers, of course, but to suggest that an English top-notch stroke during this time should not ‘power the boat’ is plain wrong. Another thing where Brown goes astray – and he comes back to it over and over again – is the crews’ starting process: that Bobby Moch, the Huskies’ cox, would raise his hand to show that his crew was ready to race, while I think that the start then was as it is to this day, the cox has his/her hand up to indicate to the umpire at the start that the crew is not ready to start. Take a good look at Oxford’s and Cambridge’s coxes at the start of the Boat Race on the Thames next time. The weather conditions and the stream are making it hard for the person in the stake boat to hold the boat. The cox is having his, or her, hand up while the bow pair is straightening up the boat to the coxswain’s liking. Rowing historian Tim Koch, a frequent HTBS contributor, writes in an e-mail about hands up or down at the start: ‘If you have not got both hands on the rudder strings, you are not ready. This is especially true in the old days of big rudders when rudder strings were very loose and had to be held “tight”.’ There are some other peculiarities of Brown’s in the book, but my points are made. However in the grand scheme of things Brown has done a good job, and we rowers are always grateful when our sport gets exposure in whatever media it might be.

It was evident, even before the book came out in June, that the book would be a success: the film rights have been bought by the Weinstein Company (see here), and when I met Brown at an event this summer, he told me that a screenwriter is working on the script, although he could not give me any details at that time.

Whenever the movie is coming out, I will line up outside the movie theatre, ready to be enchanted.

*This article was updated on 20 August, reflected the information given in Comment No. 1 by Richard A. Kendall.

Although rowing – or as it is called in America, crew – is a minor sport compared to other team games, each and every year sees a new book published about this aquatic activity. Nevertheless, it is rare to be able to add a new title to the niche genre of rowing history. Amongst the authors and the books which are still in print in this group, and worth mentioning here, you will find: David Halberstam’s The Amateurs (hardcover 1986; paperback 1996), Daniel Boyne’s two books The Red Rose Crew (2000; 2005) and Kelly: A Father, A Son, An American Quest (2008, 2012), and Christopher Dodd’s Pieces of Eight (published in Great Britain, 2012).

To this small, but splendid collection of authors and their books can now be included Daniel James Brown and his The Boys in the Boat – Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (Viking, 2013, 404 pp.). As the subtitle tells, Brown’s book is about the U.S. eight with coxswain who went to fight for honour and glory at the 1936 Olympic rowing regatta on lake Langer See at Grünau, outside Berlin, where these young American oarsmen became Olympic champions by a slim margin.

All Americans love a tale about underdogs, especially if the underdogs are Americans, and at the center of this compelling story is Joe Rantz, one of the boys in the crew, whom Brown met at his neighbour Judy Willman’s house; Judy was Joe’s daughter, and when Joe was diagnosed with cancer, he lived with her his remaining days. Listening to the old oarsman’s account, Brown realized that the story of these Olympians is not as commonly known as, for example, Jesse Owens’s, whose four golds at the Berlin Games gave the Nazis’ ideology of the Aryan race superiority a severe dent.

The sons of farmers, fishermen and lumberjacks forming the Husky crews are getting a little different ‘workout’ sawing through a big log of Douglas spruce. Photograph from 1929. Courtesy of Thomas E Weil.

While rowing back in the 1930s was regarded as a sport for the privileged few, Joe and his oarsmen comrades at the University of Washington were the sons of farmers, fishermen, and lumberjacks. Although Brown’s narrative is about all the boys in the boat – their way from freshmen on Lake Washington to Olympians on Langer See, a three- to four-year voyage not always on an easy, straight course – it is the human story of young Joe’s struggling life of Dickensian dimensions during the Depression that grabs hold of the reader.

Assisting the Husky crews was a remarkable group of rowing men: University of Washington’s head coach Al Ulbrickson, known as “the Dour Dane,” freshman coach Tom Bolles, who later became a successful coach for Harvard crews (both on the right); and boat builder George Pocock, the Englishman whose father had built boats for the “wet-bobs” at Eton College. George Pocock also helped to coach the Husky boys, using the same techniques he used to build the best racing shells in America: a philosophical approach and a sharp eye. It is as Brown writes, “Great crews are carefully balanced blends of both physical abilities and personality types.”

However, when Ulbrickson had found the perfect combination of nine men, they still had to beat the arch-rival crew from California-Berkeley, coached by Ky Ebright, whose previous crews had represented the U.S. in both the 1928 and 1932 Olympic Games. Then Joe and his mates had to overpower the “snobs” from the East Coast at the 1936 IRA Regatta at Poughkeepsie – this was a time when an incredible number of 90,000 spectators gathered on the shores of the Hudson to watch the races. In the Pocock-built Husky Clipper, the Huskies prevailed (told by the author in a beautiful race report). *Later winning the Olympic Trials in Princeton, it seemed the Washington crew had their trip to Berlin in the bag, but not before good people in Seattle and in the boys’ hometowns managed to raise $5,000 in a few days for their tickets.

In their first heat at Grünau, the Americans managed to keep the British eight at bay, forcing them to a repechage heat, an extra race which they won, taking them to the final, where strong crews from Germany and Italy were all game for the Olympic medals. It was the British boat, stroked by the eminent “Ran” Laurie and coxed by Noel Duckworth – two of my rowing heroes – that the Huskies feared most. In the final race, in front of Der Führer and other Nazi dignitaries, the Husky Clipper sneaked up from the far back of the field to snatch the gold medal, leaving the silver medal to the Italians and the bronze medal to the Germans, and the Brits with nothing, coming in fourth.

Daniel James Brown

Daniel James Brown is a clever author and it is a grand story he is telling. He is not a rower himself, which is probably good, because he has made sure that a non-rower can easily follow the Husky boys when they catch a crab or feel the pain like they do after a hard race on Lake Washington. On the other hand there are also some oddities in his narrative. About Ran Laurie, Brown writes:

In the British boat, Ran Laurie dug furiously at the water. He was still relatively fresh. He wanted to do more. But like many British strokes in those days, he was wielding an oar with a smaller, narrower blade than the rest of his crew – the idea being that the stroke’s job was to set the pace, not to power the boat. With the small blade, he avoided the risk of burning himself out and losing his form.

No, I do not think that Laurie, one of the great Cambridge strokes before the Second World War, had a more narrow blade than the rest of his crew – honestly, it would not be cricket! Oarsmen might have individually adjusted riggers, of course, but to suggest that an English top-notch stroke during this time should not ‘power the boat’ is plain wrong. Another thing where Brown goes astray – and he comes back to it over and over again – is the crews’ starting process: that Bobby Moch, the Huskies’ cox, would raise his hand to show that his crew was ready to race, while I think that the start then was as it is to this day, the cox has his/her hand up to indicate to the umpire at the start that the crew is not ready to start. Take a good look at Oxford’s and Cambridge’s coxes at the start of the Boat Race on the Thames next time. The weather conditions and the stream are making it hard for the person in the stake boat to hold the boat. The cox is having his, or her, hand up while the bow pair is straightening up the boat to the coxswain’s liking. Rowing historian Tim Koch, a frequent HTBS contributor, writes in an e-mail about hands up or down at the start: ‘If you have not got both hands on the rudder strings, you are not ready. This is especially true in the old days of big rudders when rudder strings were very loose and had to be held “tight”.’ There are some other peculiarities of Brown’s in the book, but my points are made. However in the grand scheme of things Brown has done a good job, and we rowers are always grateful when our sport gets exposure in whatever media it might be.

It was evident, even before the book came out in June, that the book would be a success: the film rights have been bought by the Weinstein Company (see here), and when I met Brown at an event this summer, he told me that a screenwriter is working on the script, although he could not give me any details at that time.

Whenever the movie is coming out, I will line up outside the movie theatre, ready to be enchanted.

*This article was updated on 20 August, reflected the information given in Comment No. 1 by Richard A. Kendall.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

The Good Omen

The Good Omen

While waiting for the Charles W. Morgan

to launch, I watched

a pair of cormorants fly north along

Mystic River,

curve east

toward where the Morgan stood,

and part in flight over her.

Philip Kuepper

(22 July, 2013)

Photo courtesy of Mystic Seaport

While waiting for the Charles W. Morgan

to launch, I watched

a pair of cormorants fly north along

Mystic River,

curve east

toward where the Morgan stood,

and part in flight over her.

Philip Kuepper

(22 July, 2013)

Photo courtesy of Mystic Seaport

Friday, August 16, 2013

1956 Olympic Eights Races

Before the 1956 Olympic rowing regatta on Lake Wendouree, Ballarat, Australia, the U.S. eight had not lost one single Olympic race since 1920, winning gold 1920, 1924, 1928, 1932, 1936, 1948 and 1952. However, when the young men from Yale raced in their first heat at Ballarat, they only managed to take a third place, beaten by Australia and Canada. Slightly embarrassed, the Yalies made sure to win the repechage heat, then winning in the semi-final, and then crossing the finish line as the first boat in the final, taking the Olympic gold. After having crossed the line, three-seated John Cooke collapsed, giving everything he had in him.

In the old, interesting video above both John Cooke and David Wight are interviewed about the races. At the Rowing History Forum, held in March 2008, Wight gave a thrilling talk about how it felt to belong to an American crew who lost an Olympic race (and despite that, becoming Olympic champions). John Cooke's 1956 Olympic oar now hangs in the NRF's National Rowing Hall of Fame at Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Steady, Steady…

New Zealand’s Julia Edward (left) and Lucy Strack have their boat balancing perfectly. © Photo Margaret Webster, Marketing and Communications Manager, Rowing New Zealand.

Like the rest of the international rowing elite, the Rowing New Zealand Women’s Lightweight Double Sculls, Julia Edward and Lucy Strack, are on their way to Chungju-si, South Korea, for the 2013 World Rowing Championships, held between 25 August and 1 September. They will have their first heat on 25 August. Before leaving Lake Karapiro Rowing High Performance Centre, the ladies were practicing balancing …. Fine job, I say!

Thanks to HTBS reader Ann Woolliams who sent the photograph.

Like the rest of the international rowing elite, the Rowing New Zealand Women’s Lightweight Double Sculls, Julia Edward and Lucy Strack, are on their way to Chungju-si, South Korea, for the 2013 World Rowing Championships, held between 25 August and 1 September. They will have their first heat on 25 August. Before leaving Lake Karapiro Rowing High Performance Centre, the ladies were practicing balancing …. Fine job, I say!

Thanks to HTBS reader Ann Woolliams who sent the photograph.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Charley Butt, New Coach for Harvard Men’s Heavyweight Crew

Charley Butt. Photo: Crimson.com

Earlier today, Harvard University Director of Athletics, Bob Scalise, announced that Charley Butt, Harvard Men’s Lightweight Coach, has been appointed the Bolles-Parker Head Coach for Harvard Men’s Heavyweight Crew. Butt will take over this position after legendary Harry Parker, who passed away on 25 June after having been the Crimson coach for 51 seasons. Read more on the Harvard crew’s website, here.

Monday, August 12, 2013

2013 World Rowing Coastal Championships in Helsingborg, Sweden

Next weekend it’s time for the 2013 World Rowing Coastal Championships, held in the beautiful city of Helsingborg, in the south of Sweden. While the Swedish organisers on their website state that these championships are held between 15 and 18 August, FISA writes in an article about this event that it’s held on 15 and 16 August. Below is a promotion video about Helsingborg and costal rowing in the city, which is organised by the local rowing club, Helsingborgs Roddklubb.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

2013 World Junior Championships - reports and results

Jessica Leyden, Great Britain's first junior world champion in the single sculls.

The 2013 World Rowing Junior Championships in Trakai, Lithuania, ended today. This regatta was the main qualification regatta for new Youth Olympic Games, YOG, which will be rowed for the first time next year, 2014. To read more about the Junior Championships, FISA has race reports and results on their web site, here.

Read what Rachel Quarrell, of the Daily Telegraph, has to say about Leyden's victory, here.

The 2013 World Rowing Junior Championships in Trakai, Lithuania, ended today. This regatta was the main qualification regatta for new Youth Olympic Games, YOG, which will be rowed for the first time next year, 2014. To read more about the Junior Championships, FISA has race reports and results on their web site, here.

Read what Rachel Quarrell, of the Daily Telegraph, has to say about Leyden's victory, here.

Friday, August 9, 2013

Rowing Early Morning

Rowing Early Morning

The chaliced sky

held the wafered sun

the river held reflected

in its clear-glass surface.

Through this the rower

drew his scull.

Philip Kuepper

(21 July, 2013)

The chaliced sky

held the wafered sun

the river held reflected

in its clear-glass surface.

Through this the rower

drew his scull.

Philip Kuepper

(21 July, 2013)

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Learn from the Legends

The Finnish Legend Pertti Karppinen in 1976.

On Monday, 5 August, HTBS's friend Bryan Kitch, of the brilliant blog Rowing Related, posted a marvellous old video in his series "Video of the Week". The good fellow Bryan also sent a tweet to HTBS (@boatsing) to make sure that we would not miss this 'education movie', showing among others Pertti Karppinen's and Peter-Michael Kolbe's sculling styles. The film, "Learning with Legends", is a true gem and we would not like any of HTBS's readers to miss it. That is why we happily direct you to Bryan's Rowing Related - enjoy, and thank you very much Bryan! Watch "Learning with Legends" here. (Seeing Karppinen sculling takes me back to the 1970s and a couple of Nordic Championships held in Denmark and Sweden where no one was able to give the Gentle Finn a match.)

On Monday, 5 August, HTBS's friend Bryan Kitch, of the brilliant blog Rowing Related, posted a marvellous old video in his series "Video of the Week". The good fellow Bryan also sent a tweet to HTBS (@boatsing) to make sure that we would not miss this 'education movie', showing among others Pertti Karppinen's and Peter-Michael Kolbe's sculling styles. The film, "Learning with Legends", is a true gem and we would not like any of HTBS's readers to miss it. That is why we happily direct you to Bryan's Rowing Related - enjoy, and thank you very much Bryan! Watch "Learning with Legends" here. (Seeing Karppinen sculling takes me back to the 1970s and a couple of Nordic Championships held in Denmark and Sweden where no one was able to give the Gentle Finn a match.)

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Guiseppe, Wally and Friends

WDK, New York Herald

Tim Koch writes,

After posting my recent piece on Guiseppe Sinigaglia and his rivalry and friendship with Wally Kinnear (particularly at the Coupe des Nations d’Aviron in Paris between 1912 and 1914), I remembered a picture archive first noted on HTBS by Hélène Rémond. The Gallica Digital Library is part of the National Library of France. Type in ‘aviron’ (rowing) and all sorts of goodies appear. The pictures can be viewed in fantastic detail as they were originally shot on large format ‘plate’ cameras and have been scanned in very high resolution. To enlarge, initially click on the magnifying glass symbol on the top left and then, in the new window, click on the magnifying glass with the plus sign on the top right.

I found a very nice picture of Sinigaglia posing in his boat at the 1913 European Championships and another of him racing on the on the Grand Terneuzen Canel on the same day.

It was also interesting to find a previously unknown picture of Wally Kinnear at the 1913 Coupe des Nations. It had been wrongly labelled as ‘the English rower Pettmann’, instead of ‘the Scottish sculler Kinnear’.

Not all the pictures are of Frenchmen. Here are two World Champions, on the left Darcy Hadfield of New Zealand, then still an amateur, and on the right, the professional sculler Ernest Barry of Great Britain.

Here is a selection of my favourite faces from the archive, chosen on character rather than rowing achievements: Gaston Delaplane photographed in July 1911; The aristocratic looking Anatol Peresselenzeff, posing in August 1913. He was a man with French and Russian connections who also sculled for Thames Rowing Club in London; I do not know who Monsieur Pichard was but I suspect that he enjoyed his sculling. A rare unposed picture; M. Horodinsky was probably tough opposition; It looks as though the stylish M. Cheval is patiently awaiting the invention of lycra.

C’est Magnifique.

Tim Koch writes,

After posting my recent piece on Guiseppe Sinigaglia and his rivalry and friendship with Wally Kinnear (particularly at the Coupe des Nations d’Aviron in Paris between 1912 and 1914), I remembered a picture archive first noted on HTBS by Hélène Rémond. The Gallica Digital Library is part of the National Library of France. Type in ‘aviron’ (rowing) and all sorts of goodies appear. The pictures can be viewed in fantastic detail as they were originally shot on large format ‘plate’ cameras and have been scanned in very high resolution. To enlarge, initially click on the magnifying glass symbol on the top left and then, in the new window, click on the magnifying glass with the plus sign on the top right.

I found a very nice picture of Sinigaglia posing in his boat at the 1913 European Championships and another of him racing on the on the Grand Terneuzen Canel on the same day.

It was also interesting to find a previously unknown picture of Wally Kinnear at the 1913 Coupe des Nations. It had been wrongly labelled as ‘the English rower Pettmann’, instead of ‘the Scottish sculler Kinnear’.

Not all the pictures are of Frenchmen. Here are two World Champions, on the left Darcy Hadfield of New Zealand, then still an amateur, and on the right, the professional sculler Ernest Barry of Great Britain.

Here is a selection of my favourite faces from the archive, chosen on character rather than rowing achievements: Gaston Delaplane photographed in July 1911; The aristocratic looking Anatol Peresselenzeff, posing in August 1913. He was a man with French and Russian connections who also sculled for Thames Rowing Club in London; I do not know who Monsieur Pichard was but I suspect that he enjoyed his sculling. A rare unposed picture; M. Horodinsky was probably tough opposition; It looks as though the stylish M. Cheval is patiently awaiting the invention of lycra.

C’est Magnifique.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

A Victorian Ladder: Eton College at Henley

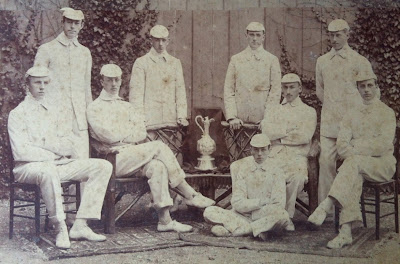

A Victorian ladder

HTBS’s Greg Denieffe writes,

In an earlier post on HTBS called “Toad, Tom, Jack and Billy!”, I mentioned that I had researched the story of The Rowing Bunburys of Lisnavagh. Recently, Turtle Bunbury sent me some old photographs that he found in the archives of the Bunbury family home at Lisnavagh House, Rathvilly, County Carlow.

Included was the wonderful but undated photograph on top described by Turtle as a Victorian Ladder. There is no mistaking the trophy which is The Ladies’ Plate from Henley Royal Regatta and I think the photograph is of the 1896 winning crew from Eton College. What do other HTBS readers think?

If, as I would expect, they are recreating the positions of the crew when they are in the boat, then the names from top to bottom would be as follows:

Bow Hon. M. C. A. Drummond

2 C. M. Black

3 F. W. Warre

4 E. L. Warre

5 J. L. Philips

6 J. A. Tinne

7 W. Dudley Ward

Str. Hon. W. McClintock Bunbury

Cox R. A. Blyth

Stroke of the 1896 crew and standing behind the seated coxswain would be Hon. W. McClintock Bunbury, known to his family and friends as Billy Bunbury (1878-1900). Can you see a similarity to the young boy in the ladder?

William McClintock Bunbury was born at Lisnavagh in 1878, the eldest son of Thomas Kane (Tom) McClintock Bunbury, 2nd Baron Rathdonnell, and his wife, Lady Katherine Anne (Kate) Rathdonnell. Billy was educated at the Dragon School in Oxford and Eton College [April 1892 – December 1897] where he was in Rev S. A. Donaldson’s House. Donaldson was successor to Rev Edmund Warre and like him an enthusiastic rowing coach. As was his father before him, Billy was captain of boats at Eton and stroked the winning Ladies’ Plate crews of 1896 and 1897. He joined the Scots Greys shortly after leaving Eton. He was posted to South Africa in December 1899 and died ten weeks later, on the 17 February, 1900, having been shot in both legs in a raid on a Boer position eight miles outside Kimberley.

In the seven-seat and standing behind Billy Bunbury would be William Dudley Ward (1877-1946), one of the rowers depicted in The Rowers of Vanity Fair.

William Dudley Ward, ‘seven’ in 1896 - Famous for having a far-away-look in his eyes! (© National Portrait Gallery, London. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.)

In the three-seat and third from the top would be Felix Warre (1879–1953) depicted above in the Illustrated London News in 1898 as part of the Oxford University Boat Race crew.

Also included in the Bunbury archives was a photograph, again undated, but a similar photograph on the Balliol College website identifies the race as the final of the Ladies’ Challenge Plate in 1896:

Photo [C. R. Dunlop, Balliol College, Oxford] reproduced by kind permission of Balliol College.

Two photographs were identified as from Henley. The one above is in good condition and was captioned: Ladies’ Plate 1896 – Eton & Jesus (Oxford).

This one was also captioned: Henley Regatta 1896, Ladies Plate Final, Eton v Balliol – Billy stroke Eton.

The official result of the final was that Eton College beat Balliol College, Oxford by 2½ lengths in a time of 8 min. 6 sec.

Here is another undated photograph, again showing the trophy for the Ladies’ Plate. Seated second left is probably John William McClintock Bunbury (Jack Bunbury), 1851 - 1893.

Jack’s first success at Henley Royal Regatta was in the two seat of the Eton crew that won the Ladies’ Plate in 1868. The boat was stroked by his brother Tom and for the next two years Jack would stroke the Eton eight to two more victories in the same event.

After finishing at Eton College in 1870 Jack went up to Oxford University where he quickly joined the Brasenose College Boat Club, the oldest collegiate boat club in the world. In his short stay at the university, he won The Trial Eights (1870), The Silver Sculls (1871) and The Silver Challenge Oars for pairs (1871).

Jack Bunbury as depicted in the Illustrated London News in 1871 as part of the Oxford University Boat Race crew.

Jack was originally selected in the stroke seat of the Oxford crew for the 1871 Boat Race but was switched to the seven-seat close to race day. It seems to have worked better for them and by March 18, the Penny Illustrated favoured Oxford over Cambridge. On Saturday, 1 April, the two crews set off but it was Cambridge who, despite a last minute spurt by the Oxford crew by the Mortlake brewery, won by a length in 23 min. and 5 sec. (‘with a foul wind from the north east’).

At Henley in July 1871, Jack was defeated by Mr. William Fawcus of the Tynemouth Rowing Club, shortly before Fawcus defeated Mr. Long, the winner of the Wingfield Sculls. Jack was also in the four seat of the Oxford Etonians crew that won the Grand Challenge Cup. This was the sixth and final time that the Eton old boys would win the premier event at the premier regatta in the country. It was Jack’s finest hour in a boat and probably his last. The up-and-coming London Rowing Club was beaten in the final by 1½ lengths in a time of 8 min. 5sec.

Jack was only at Oxford until December 1871 when he left to pursue a career in the army. Sadly, he died in 1893 at the age of only 42 and was buried in the graveyard at St. Helen’s Church, Tarporley, Cheshire.

Maybe other HTBS readers can help positively identify the undated photographs and their subjects?

There were a few more photographs found at Lisnavagh but they are of rather poor quality and undated. The following photo is clearly the Eton College boathouses and perhaps there is a Bunbury in the crew. The close-up shows the presence of the photographer was indeed an occasion that the boys were not going to miss.

Thanks to Turtle Bunbury for sending these interesting photographs.

Monday, August 5, 2013

Guiseppe Sinigaglia – ‘The ‘Italian Giant’

Guiseppe Sinigaglia – ‘The ‘Italian Giant’.

Tim Koch writes,

HTBS of 29 July asked, "Is the Mystery Man the Champion Sculler Guiseppe Sinigaglia?" The answer is ‘No’. Sinigaglia was 14 stone 10 pounds (93.5 kg / 206 pounds) and 6 foot 4 inches (193 cms). This is big for modern times. By the standards of the turn of the century he was, in the words of The Times newspaper, ‘the Italian Giant’. The man in the picture is of average (or even below average) size compared to everyone else in the photograph.

What I know of Guiseppe Sinigaglia comes through my researches on the career of William ‘Wally’ Kinnear (1880-1974) the world’s best sculler in the period 1910 to 1913. The paths of the two men crossed several times.

Kinnear raced in the Coupe des Nations d’Aviron, a 4,000-metre race on the Seine in Paris, in 1912, 1913 and 1914. Though 14 lbs / 12 kg lighter and 4 inches / 10 cms shorter, he beat Sinigaglia to second place in the first two races but lost to him in 1914, claiming that a tug washed him down for part of the way. The French newspaper Le Martin reported on the 1913 race:

Kinnear showed his imposing superiority. He defeated his competition without rushing, when it suited him.

In 1965 Kinnear recalled his first Coupe des Nations in an interview recorded on audio tape by his son, Donald:

.... I met an Italian called Sinigaglia, a big 6 foot 4 man, 14 1/2 stone... to cut a long story short, I beat him. Before the race on the Seine I was introduced to a man called Deperdussin. He had a big factory on the river, he made all sorts of aircraft... He said to me if you beat this Italian I’ll present you with one of my sculling boats.... His warehouse or factory was a mile from the start and when I passed his place I was just been beaten by Sinigaglia, he went by me and I thought ‘there goes my French sculling boat’. Anyway I stuck to Sinigaglia and after another half mile .... I looked to my right hand side and there he was, beaten, stopped and that’s how I won my first Coupe de Nations.

W.D. Kinnear after winning the Coup des Nations d’Aviron in 1913. The legs are not obviously those of a champion.

Kinnear then recalled what happened after he lost in Paris in 1914:

.... Sinigaglia asked me if I was going for (Henley’s Diamond Sculls) after that, I said no I’m not, I’m finished sculling at home. So he came over for the Diamonds..... and in the final he met the man who had beat me in the first heat in 1912 when I was stale, a chap that I could scull rings round.

This was C.M. Stuart. There follows a long story about the victorious Stuart boasting that ‘he knew that he could do it’ while not acknowledging that Kinnear was over-trained in preparation for the upcoming Stockholm Olympics. Fifty years on, Kinnear was still rankled and clearly contemptuous of Stuart:

.....for the final of the (1914) Diamonds it had turned a bit cold, very cold, and being an Italian he.., they don't like cold weather... his advisor and trainer came up to me and said Sinigaglia refuses to go out for the final, he’s sitting there and you must come and talk to him.... I couldn’t talk Italian, I could talk English in my own way, and I said to his trainer, you tell him that he's a bloody coward. He told him and he flared up in a Italian way and he had to keep him off me and I said, all right just you go out, you’ve got Stuart... what are you worrying about, just because he beat me, you think you’ve got something to do, you’ve got nothing to do. All you’ve got to do is listen for my voice half way over the course and I’ll shout out ‘Now Sinigaglia!’ in my own way and you’ll hear that. Well he went, he came down the course, he was leading off the mark and he led for just a few hundred yards up the river and then he let Stuart go sailing by and Stuart was as white as a sheet and I said ‘Now Sinigaglia’ (laughs) and he just opened up and went by him and beat him anyhow. From that day I felt that I should not have done that, there was a feeling against me for some time, they had just felt that I had sponsored an Italian to win the Diamonds and beat an Englishman at Henley. But I’ve got reasons of my own for that...

Thus Kinnear claimed a share of the credit for Sinigaglia’s victory. The idea that he would not go out because it was cold seems a little unlikely but Johan ten Berg writes that Sinigaglia ‘is mentioned as one of the entries (in the 1912 Holland Beker), but as he isn’t mentioned in the results in the newspapers, he may not have started’. Johan continues, ‘In another article it states that Gerhard Nunninghof, Kölner Club für Wassersport, won a heat on walk-over as Sinigaglia did not show up at the start’. Thus the man did have a record of not turning up for his races. Nowadays, he would perhaps be treated by a sports psychologist.

More certain is that the Henley programme had the big man at 14 stone 10 pounds (93.5 kg / 206 pounds) while Stuart was down as 11 stone (70 kg / 154 pounds) so it is arguable that the Italian would have eventually passed the Englishman even without Kinnear’s inspiring call (which in any case would be rather difficult to hear on the water). Further, the account of the race in The Times newspaper of 6 July 1914 does not fully agree with Kinnear’s version:

Stuart, who rowed 37 strokes in his first minute, dashed off with the lead, the Italian doing 38. Sinigaglia hit the piles at the top of the Island and this enabled Stuart to lead by two lengths at the quarter mile. Sinigaglia reduced this by half a length at the next signal and, spurting hard, was nearly level at Fawley. A great race followed to the mile. Stuart answered his opponent’s spurts and kept just ahead. Sinigaglia sculled with great power and at the lower end of the Enclosure Stuart suddenly stopped, completely rowed out and had to be lifted from his boat onto the umpire’s launch. Sinigaglia finished alone.

(Sinigaglia’s Henley opponents had a hard time of it. In a heat against Dibble of Don Rowing Club, Toronto, on 3 July, the Canadian fell out of his boat at the finish and had to be rescued by the umpire).

The newspaper report on the final may be more accurate than Kinnear’s recollections but is not such a good story. There is a poignant conclusion to the Wally’s memories of France in the summer of 1914:

I had a good time in Paris. An English gentleman, a millionaire, took me all over the place... We had a wonderful time... we were having lunch on the Marne, on the lawn having Champagne with this gentleman and within a month the Germans had overrun this part...

Within two years of the outbreak of the First World War, Guiseppe Sinigaglia, ‘the Italian Giant’, the winner of the 1914 Coup des Nations and of the 1914 Diamond Sculls would be dead – along with millions of others. It must have seemed that ‘Champagne on the lawn’ had ended forever.

Le Martin, 4 June 1912. The order of the Coup des Nations at this stage is probably the French-Russian, Peressenlenzeff in the lead followed by Sinigaglia and then Kinnear.

Tim Koch writes,

HTBS of 29 July asked, "Is the Mystery Man the Champion Sculler Guiseppe Sinigaglia?" The answer is ‘No’. Sinigaglia was 14 stone 10 pounds (93.5 kg / 206 pounds) and 6 foot 4 inches (193 cms). This is big for modern times. By the standards of the turn of the century he was, in the words of The Times newspaper, ‘the Italian Giant’. The man in the picture is of average (or even below average) size compared to everyone else in the photograph.

What I know of Guiseppe Sinigaglia comes through my researches on the career of William ‘Wally’ Kinnear (1880-1974) the world’s best sculler in the period 1910 to 1913. The paths of the two men crossed several times.

Kinnear raced in the Coupe des Nations d’Aviron, a 4,000-metre race on the Seine in Paris, in 1912, 1913 and 1914. Though 14 lbs / 12 kg lighter and 4 inches / 10 cms shorter, he beat Sinigaglia to second place in the first two races but lost to him in 1914, claiming that a tug washed him down for part of the way. The French newspaper Le Martin reported on the 1913 race:

Kinnear showed his imposing superiority. He defeated his competition without rushing, when it suited him.

In 1965 Kinnear recalled his first Coupe des Nations in an interview recorded on audio tape by his son, Donald:

.... I met an Italian called Sinigaglia, a big 6 foot 4 man, 14 1/2 stone... to cut a long story short, I beat him. Before the race on the Seine I was introduced to a man called Deperdussin. He had a big factory on the river, he made all sorts of aircraft... He said to me if you beat this Italian I’ll present you with one of my sculling boats.... His warehouse or factory was a mile from the start and when I passed his place I was just been beaten by Sinigaglia, he went by me and I thought ‘there goes my French sculling boat’. Anyway I stuck to Sinigaglia and after another half mile .... I looked to my right hand side and there he was, beaten, stopped and that’s how I won my first Coupe de Nations.

W.D. Kinnear after winning the Coup des Nations d’Aviron in 1913. The legs are not obviously those of a champion.

Kinnear then recalled what happened after he lost in Paris in 1914:

.... Sinigaglia asked me if I was going for (Henley’s Diamond Sculls) after that, I said no I’m not, I’m finished sculling at home. So he came over for the Diamonds..... and in the final he met the man who had beat me in the first heat in 1912 when I was stale, a chap that I could scull rings round.

This was C.M. Stuart. There follows a long story about the victorious Stuart boasting that ‘he knew that he could do it’ while not acknowledging that Kinnear was over-trained in preparation for the upcoming Stockholm Olympics. Fifty years on, Kinnear was still rankled and clearly contemptuous of Stuart:

.....for the final of the (1914) Diamonds it had turned a bit cold, very cold, and being an Italian he.., they don't like cold weather... his advisor and trainer came up to me and said Sinigaglia refuses to go out for the final, he’s sitting there and you must come and talk to him.... I couldn’t talk Italian, I could talk English in my own way, and I said to his trainer, you tell him that he's a bloody coward. He told him and he flared up in a Italian way and he had to keep him off me and I said, all right just you go out, you’ve got Stuart... what are you worrying about, just because he beat me, you think you’ve got something to do, you’ve got nothing to do. All you’ve got to do is listen for my voice half way over the course and I’ll shout out ‘Now Sinigaglia!’ in my own way and you’ll hear that. Well he went, he came down the course, he was leading off the mark and he led for just a few hundred yards up the river and then he let Stuart go sailing by and Stuart was as white as a sheet and I said ‘Now Sinigaglia’ (laughs) and he just opened up and went by him and beat him anyhow. From that day I felt that I should not have done that, there was a feeling against me for some time, they had just felt that I had sponsored an Italian to win the Diamonds and beat an Englishman at Henley. But I’ve got reasons of my own for that...

Thus Kinnear claimed a share of the credit for Sinigaglia’s victory. The idea that he would not go out because it was cold seems a little unlikely but Johan ten Berg writes that Sinigaglia ‘is mentioned as one of the entries (in the 1912 Holland Beker), but as he isn’t mentioned in the results in the newspapers, he may not have started’. Johan continues, ‘In another article it states that Gerhard Nunninghof, Kölner Club für Wassersport, won a heat on walk-over as Sinigaglia did not show up at the start’. Thus the man did have a record of not turning up for his races. Nowadays, he would perhaps be treated by a sports psychologist.

More certain is that the Henley programme had the big man at 14 stone 10 pounds (93.5 kg / 206 pounds) while Stuart was down as 11 stone (70 kg / 154 pounds) so it is arguable that the Italian would have eventually passed the Englishman even without Kinnear’s inspiring call (which in any case would be rather difficult to hear on the water). Further, the account of the race in The Times newspaper of 6 July 1914 does not fully agree with Kinnear’s version:

Stuart, who rowed 37 strokes in his first minute, dashed off with the lead, the Italian doing 38. Sinigaglia hit the piles at the top of the Island and this enabled Stuart to lead by two lengths at the quarter mile. Sinigaglia reduced this by half a length at the next signal and, spurting hard, was nearly level at Fawley. A great race followed to the mile. Stuart answered his opponent’s spurts and kept just ahead. Sinigaglia sculled with great power and at the lower end of the Enclosure Stuart suddenly stopped, completely rowed out and had to be lifted from his boat onto the umpire’s launch. Sinigaglia finished alone.

(Sinigaglia’s Henley opponents had a hard time of it. In a heat against Dibble of Don Rowing Club, Toronto, on 3 July, the Canadian fell out of his boat at the finish and had to be rescued by the umpire).

The newspaper report on the final may be more accurate than Kinnear’s recollections but is not such a good story. There is a poignant conclusion to the Wally’s memories of France in the summer of 1914:

I had a good time in Paris. An English gentleman, a millionaire, took me all over the place... We had a wonderful time... we were having lunch on the Marne, on the lawn having Champagne with this gentleman and within a month the Germans had overrun this part...

Within two years of the outbreak of the First World War, Guiseppe Sinigaglia, ‘the Italian Giant’, the winner of the 1914 Coup des Nations and of the 1914 Diamond Sculls would be dead – along with millions of others. It must have seemed that ‘Champagne on the lawn’ had ended forever.

Le Martin, 4 June 1912. The order of the Coup des Nations at this stage is probably the French-Russian, Peressenlenzeff in the lead followed by Sinigaglia and then Kinnear.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

The Architecture of Rowing

The Architecture of Rowing

Stood on its end, the oar,

being twisted back and forth

by the rower waiting ashore

for the shell to be placed in the water,

caused my mind imagine

he was twisting a skinny version

of Malmö's Turning Torso.

Philip Kuepper

(July 2013)

Stood on its end, the oar,

being twisted back and forth

by the rower waiting ashore

for the shell to be placed in the water,

caused my mind imagine

he was twisting a skinny version

of Malmö's Turning Torso.

Philip Kuepper

(July 2013)

Saturday, August 3, 2013

On Irish Oarsman Niall O'Toole

Here is a great interview by Turtle Bunbury on the Irish Olympic rower and sculler, Niall O'Toole, the first Irishman to become World Champion in rowing. Read Bunbury's piece here.

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Lions not Donkeys

An early First World War recruitment poster. There was no official ‘Oarsman's Battalion’ but some crews joined their local regiment en masse. The idea that war was ‘the greater game’ could not have lasted very long.

Tim Koch writes from London,

This week marks the 99th Anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. The actual day is open to choice. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July, 1914. Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August and on France on 2 August. Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August.

During the period 1914 to 1918, five million British men served in the armed forces. Initially they were all volunteers and conscription was not introduced until seventeen months into the conflict. The poplar view of the early months of the war is of young men desperate to join up in case hostilities ended before they could take part in a great adventure. Adventure may not have been everyone’s reason for joining the ‘citizens’ army’ as there was also enormous peer pressure from workplaces, friends, families, sports clubs, schools, colleges and social groups. Whatever their reasons, oarsmen would have been among the first to join up. They were young and fit and had a bond with their crew mates that only one of the ultimate team sports can produce. Sadly, for many the 1914 rowing season was to be their last.

My own club, now called Auriol Kensington, has pictures of two 1914 crews on its walls. The Kensington Junior Eight that won at Molesey lost four members by 1918 and the Auriol eight that raced at Henley lost three. In all, both clubs lost a total of twenty-four men who were members at the outbreak of the War. This would not be untypical.

The memorials subsequently erected to by clubs to remember their crew mates killed is a subject that HTBS has covered several times. We have noted those in Thames RC, Auriol Kensington RC, Vesta RC, and Marlow RC. While it is common for British rowing clubs have war memorials, on my recent visit to Vancouver Rowing Club (VRC) in Canada, I was reminded of the sacrifices made by men from what was then the British Empire. VRC has a bronze plaque listing the names of the 164 men who volunteered for active service including the 38 who were wounded and the 38 who were killed, a death rate of twenty-three per cent.

The list of those members of Vancouver RC who served in the 1914-1918 War. Those marked with a star were killed, those marked with a bar were wounded. A similar memorial exists for the 1939-1945 War. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Back home, I have recently become aware of an oarsmen’s memorial that has two differences to any others that I know of in the UK. First, it commemorates those rowers killed not from a club but from a city, and second, it is sited outside, not in a clubhouse.

The Nottingham Oarsmen’s War Memorial.

Detail from the Nottingham Memorial.

Trent Bridge crosses the River Trent in the city of Nottingham in the English East Midlands. On the north side of the bridge is a First World War memorial to fifty-five men of the four rowing clubs that existed in the city at that time. They were Nottingham Union RC, Nottingham RC (1862), Nottingham Boat Club (1894) and Nottingham Britannia RC (1869). The first two amalgamated in 1946 to form Nottingham and Union Rowing Club while the second two amalgamated in 2006 to form Nottingham Rowing Club (along with Nottingham Schools Rowing Association and the Nottinghamshire County Rowing Association).

The Memorial and a wider view of its place over the River Trent.

Examining the military ranks listed on the memorial is interesting and perhaps gives some indication of the social makeup of the Nottingham clubs. The fifty-five are made up of fourteen private soldiers, five non-commissioned officers (sergeants and corporals), twenty-eight 2nd Lieutenants and Lieutenants, five captains and three majors. Thus half were the most junior commissioned officers, that is 2nd lieutenants and lieutenants, men who led a platoon of fifty soldiers.

In his 2010 book, Six Weeks – The Short & Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), John Lewis-Stempel attempts to disassociate the junior officers from the seemingly idiotic high ranking officers who appeared to have no ideas beyond sending wave after wave of men headlong into machine gun fire (‘lions led by donkeys’). Lewis-Stempel says that the two most junior officer ranks often suffered a casualty rate twice that of private soldiers and that their average life expectancy on the front line was six weeks. Until 1917 they mostly came from public (which in the UK means private) schools. The top fee paying schools had casualty rates of twenty per cent. In four years, 1,157 Old Etonians were killed (though as the War went on and the ‘officer class’ was rapidly decimated, ‘temporary gentlemen’ from middle and working class backgrounds had to fill the void).

One of forty-two Rowing Blues killed in the First World War: Captain W.H. Chapman rowed for Cambridge in 1899, 1902 and 1903. He was killed at the Dardanelles in 1915.

That the upper classes suffered disproportionally can also be seen in the casualty rates of those oarsmen who were obviously from socially privileged backgrounds. This forum lists the forty-two Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who were killed, all of them officers. The book Henley Races by Sir Theodore Cook (Oxford University Press 1919) is available online and lists the two hundred and seventy Henley competitors who are known to have died. In both lists, half were 2nd Lieutenants and Lieutenants with thirty per cent holding the rank of captain. The Oxford-Cambridge split is exactly half. A deadly noblesse oblige.

My thanks to Ian Scothern for taking the Nottingham pictures for me. Also, some may have noticed the second name on the memorial, that of Albert Ball VC, a First World War ‘Ace’. I am investigating further but I suspect that Ball’s connection with NRC may have been somewhat tenuous.

Tim Koch writes from London,

This week marks the 99th Anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. The actual day is open to choice. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July, 1914. Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August and on France on 2 August. Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August.

During the period 1914 to 1918, five million British men served in the armed forces. Initially they were all volunteers and conscription was not introduced until seventeen months into the conflict. The poplar view of the early months of the war is of young men desperate to join up in case hostilities ended before they could take part in a great adventure. Adventure may not have been everyone’s reason for joining the ‘citizens’ army’ as there was also enormous peer pressure from workplaces, friends, families, sports clubs, schools, colleges and social groups. Whatever their reasons, oarsmen would have been among the first to join up. They were young and fit and had a bond with their crew mates that only one of the ultimate team sports can produce. Sadly, for many the 1914 rowing season was to be their last.

My own club, now called Auriol Kensington, has pictures of two 1914 crews on its walls. The Kensington Junior Eight that won at Molesey lost four members by 1918 and the Auriol eight that raced at Henley lost three. In all, both clubs lost a total of twenty-four men who were members at the outbreak of the War. This would not be untypical.

The memorials subsequently erected to by clubs to remember their crew mates killed is a subject that HTBS has covered several times. We have noted those in Thames RC, Auriol Kensington RC, Vesta RC, and Marlow RC. While it is common for British rowing clubs have war memorials, on my recent visit to Vancouver Rowing Club (VRC) in Canada, I was reminded of the sacrifices made by men from what was then the British Empire. VRC has a bronze plaque listing the names of the 164 men who volunteered for active service including the 38 who were wounded and the 38 who were killed, a death rate of twenty-three per cent.

The list of those members of Vancouver RC who served in the 1914-1918 War. Those marked with a star were killed, those marked with a bar were wounded. A similar memorial exists for the 1939-1945 War. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Back home, I have recently become aware of an oarsmen’s memorial that has two differences to any others that I know of in the UK. First, it commemorates those rowers killed not from a club but from a city, and second, it is sited outside, not in a clubhouse.

The Nottingham Oarsmen’s War Memorial.

Detail from the Nottingham Memorial.

Trent Bridge crosses the River Trent in the city of Nottingham in the English East Midlands. On the north side of the bridge is a First World War memorial to fifty-five men of the four rowing clubs that existed in the city at that time. They were Nottingham Union RC, Nottingham RC (1862), Nottingham Boat Club (1894) and Nottingham Britannia RC (1869). The first two amalgamated in 1946 to form Nottingham and Union Rowing Club while the second two amalgamated in 2006 to form Nottingham Rowing Club (along with Nottingham Schools Rowing Association and the Nottinghamshire County Rowing Association).

The Memorial and a wider view of its place over the River Trent.

Examining the military ranks listed on the memorial is interesting and perhaps gives some indication of the social makeup of the Nottingham clubs. The fifty-five are made up of fourteen private soldiers, five non-commissioned officers (sergeants and corporals), twenty-eight 2nd Lieutenants and Lieutenants, five captains and three majors. Thus half were the most junior commissioned officers, that is 2nd lieutenants and lieutenants, men who led a platoon of fifty soldiers.

In his 2010 book, Six Weeks – The Short & Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), John Lewis-Stempel attempts to disassociate the junior officers from the seemingly idiotic high ranking officers who appeared to have no ideas beyond sending wave after wave of men headlong into machine gun fire (‘lions led by donkeys’). Lewis-Stempel says that the two most junior officer ranks often suffered a casualty rate twice that of private soldiers and that their average life expectancy on the front line was six weeks. Until 1917 they mostly came from public (which in the UK means private) schools. The top fee paying schools had casualty rates of twenty per cent. In four years, 1,157 Old Etonians were killed (though as the War went on and the ‘officer class’ was rapidly decimated, ‘temporary gentlemen’ from middle and working class backgrounds had to fill the void).

One of forty-two Rowing Blues killed in the First World War: Captain W.H. Chapman rowed for Cambridge in 1899, 1902 and 1903. He was killed at the Dardanelles in 1915.

That the upper classes suffered disproportionally can also be seen in the casualty rates of those oarsmen who were obviously from socially privileged backgrounds. This forum lists the forty-two Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who were killed, all of them officers. The book Henley Races by Sir Theodore Cook (Oxford University Press 1919) is available online and lists the two hundred and seventy Henley competitors who are known to have died. In both lists, half were 2nd Lieutenants and Lieutenants with thirty per cent holding the rank of captain. The Oxford-Cambridge split is exactly half. A deadly noblesse oblige.

My thanks to Ian Scothern for taking the Nottingham pictures for me. Also, some may have noticed the second name on the memorial, that of Albert Ball VC, a First World War ‘Ace’. I am investigating further but I suspect that Ball’s connection with NRC may have been somewhat tenuous.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

)